虚拟机

Magicians protect their secrets not because the secrets are large and important, but because they are so small and trivial. The wonderful effects created on stage are often the result of a secret so absurd that the magician would be embarrassed to admit that that was how it was done.

魔术师们之所以保护他们的秘密,并不是因为秘密很大、很重要,而是它们是如此小而微不足道。在舞台上创造出的奇妙效果往往源自于一个荒谬的小秘密,以至于魔术师都不好意思承认这是如何完成的。

Christopher Priest, The Prestige

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about how to represent a program as a sequence of bytecode instructions, but it feels like learning biology using only stuffed, dead animals. We know what instructions are in theory, but we’ve never seen them in action, so it’s hard to really understand what they do. It would be hard to write a compiler that outputs bytecode when we don’t have a good understanding of how that bytecode behaves. 我们已经花了很多时间讨论如何将程序表示为字节码指令序列,但是这感觉像是只用填充的死动物来学习生物学。我们知道理论上的指令是什么,但我们在实际操作中从未见过,因此很难真正理解指令的 作用 。如果我们不能很好地理解字节码的行为方式,就很难编写输出字节码的编译器。

So, before we go and build the front end of our new interpreter, we will begin with the back end—the virtual machine that executes instructions. It breathes life into the bytecode. Watching the instructions prance around gives us a clearer picture of how a compiler might translate the user’s source code into a series of them. 因此,在构建新解释器的前端之前,我们先从后端开始—执行指令的虚拟机。它为字节码注入了生命。通过观察这些指令的运行,我们可以更清楚地了解编译器如何将用户的源代码转换成一系列的指令。

15 . 1指令执行机器

The virtual machine is one part of our interpreter’s internal architecture. You hand it a chunk of code—literally a Chunk—and it runs it. The code and data structures for the VM reside in a new module. 虚拟机是我们解释器内部结构的一部分。你把一个代码块交给它,它就会运行这块代码。VM的代码和数据结构放在一个新的模块中。

create new file

#ifndef clox_vm_h #define clox_vm_h #include "chunk.h" typedef struct { Chunk* chunk; } VM; void initVM(); void freeVM(); #endif

As usual, we start simple. The VM will gradually acquire a whole pile of state it needs to keep track of, so we define a struct now to stuff that all in. Currently, all we store is the chunk that it executes. 跟之前一样,我们从简单的部分开始。VM会逐步获取到一大堆它需要跟踪的状态,所以我们现在定义一个结构,把这些状态都塞进去。目前,我们只存储它执行的代码块。

Like we do with most of the data structures we create, we also define functions to create and tear down a VM. Here’s the implementation: 与我们创建的大多数数据结构类似,我们也会定义用来创建和释放虚拟机的函数。下面是其对应实现:

create new file

#include "common.h" #include "vm.h" VM vm; void initVM() { } void freeVM() { }

OK, calling those functions “implementations” is a stretch. We don’t have any interesting state to initialize or free yet, so the functions are empty. Trust me, we’ll get there. 好吧,把这些函数称为“实现”有点牵强了。我们目前还没有任何感兴趣的状态需要初始化或释放,所以这些函数是空的。相信我,我们终会实现它的。

The slightly more interesting line here is that declaration of vm. This module

is eventually going to have a slew of functions and it would be a chore to pass

around a pointer to the VM to all of them. Instead, we declare a single global

VM object. We need only one anyway, and this keeps the code in the book a little

lighter on the page.

这里稍微有趣的一行是vm的声明。这个模块最终会有一系列的函数,如果要将一个指向VM的指针传递给所有的函数,那就太麻烦了。相反,我们声明了一个全局VM对象。反正我们只需要一个虚拟机对象,这样可以让本书中的代码在页面上更轻便。

Before we start pumping fun code into our VM, let’s go ahead and wire it up to the interpreter’s main entrypoint. 在我们开始向虚拟机中添加有效代码之前,我们先将其连接到解释器的主入口点。

int main(int argc, const char* argv[]) {

in main()

initVM();

Chunk chunk;

We spin up the VM when the interpreter first starts. Then when we’re about to exit, we wind it down. 当解释器第一次启动时,我们也启动虚拟机。然后当我们要退出时,我们将其关闭。

disassembleChunk(&chunk, "test chunk");

in main()

freeVM();

freeChunk(&chunk);

One last ceremonial obligation: 最后一项仪式性任务:

#include "debug.h"

#include "vm.h"

int main(int argc, const char* argv[]) {

Now when you run clox, it starts up the VM before it creates that hand-authored chunk from the last chapter. The VM is ready and waiting, so let’s teach it to do something. 现在如果你运行clox,它会先启动虚拟机,再创建上一章中的手写代码块。虚拟机已经就绪了,我们来教它一些事情吧。

15 . 1 . 1执行指令

The VM springs into action when we command it to interpret a chunk of bytecode. 当我们命令VM解释一个字节码块时,它就会开始启动了。

disassembleChunk(&chunk, "test chunk");

in main()

interpret(&chunk);

freeVM();

This function is the main entrypoint into the VM. It’s declared like so: 这个函数是进入VM的主要入口。它的声明如下:

void freeVM();

add after freeVM()

InterpretResult interpret(Chunk* chunk);

#endif

The VM runs the chunk and then responds with a value from this enum: VM会运行字节码块,然后返回下面枚举中的一个值作为响应:

} VM;

add after struct VM

typedef enum { INTERPRET_OK, INTERPRET_COMPILE_ERROR, INTERPRET_RUNTIME_ERROR } InterpretResult;

void initVM(); void freeVM();

We aren’t using the result yet, but when we have a compiler that reports static errors and a VM that detects runtime errors, the interpreter will use this to know how to set the exit code of the process. 我们现在还不会使用这个结果,但是当我们有一个报告静态错误的编译器和检测运行时错误的VM时,解释器会通过它来知道如何设置进程的退出代码。

We’re inching towards some actual implementation. 我们正逐步走向一些真正的实现。

add after freeVM()

InterpretResult interpret(Chunk* chunk) { vm.chunk = chunk; vm.ip = vm.chunk->code; return run(); }

First, we store the chunk being executed in the VM. Then we call run(), an

internal helper function that actually runs the bytecode instructions. Between

those two parts is an intriguing line. What is this ip business?

首先,我们在虚拟机中存储正在执行的块。然后我们调用run(),这是一个内部辅助函数,实际运行字节码指令。在这两部分之间,有一条耐人寻味的线。这个ip作用是什么?

As the VM works its way through the bytecode, it keeps track of where it is—the location of the instruction currently being executed. We don’t use a local variable inside run() for this because eventually

other functions will need to access it. Instead, we store it as a field in VM.

当虚拟机运行字节码时,它会记录它在哪里—即当前执行的指令所在的位置。我们没有在run()方法中使用局部变量来进行记录,因为最终其它函数也会访问该值。相对地,我们将其作为一个字段存储在VM中。

typedef struct {

Chunk* chunk;

in struct VM

uint8_t* ip;

} VM;

Its type is a byte pointer. We use an actual real C pointer pointing right into the middle of the bytecode array instead of something like an integer index because it’s faster to dereference a pointer than look up an element in an array by index. 它的类型是一个字节指针。我们使用一个真正的C指针指向字节码数组的中间,而不是使用类似整数索引这种方式,这是因为对指针的引用比通过索引查找数组中的一个元素要更快。

The name “IP” is traditional, and—unlike many traditional names in CS—actually makes sense: it’s an instruction pointer. Almost every instruction set in the world, real and virtual, has a register or variable like this. “IP”这个名字很传统,而且与CS中的很多传统名称不同的是,它是有实际意义的:它是一个指令指针。几乎世界上所有的指令集,不管是真实的还是虚拟的,都有一个类似的寄存器或变量。

We initialize ip by pointing it at the first byte of code in the chunk. We

haven’t executed that instruction yet, so ip points to the instruction about

to be executed. This will be true during the entire time the VM is running: the

IP always points to the next instruction, not the one currently being handled.

我们通过将ip指向块中的第一个字节码来对其初始化。我们还没有执行该指令,所以ip指向 即将执行 的指令。在虚拟机执行的整个过程中都是如此:IP总是指向下一条指令,而不是当前正在处理的指令。

The real fun happens in run().

真正有趣的部分在run()中。

add after freeVM()

static InterpretResult run() { #define READ_BYTE() (*vm.ip++) for (;;) { uint8_t instruction; switch (instruction = READ_BYTE()) { case OP_RETURN: { return INTERPRET_OK; } } } #undef READ_BYTE }

This is the single most important function in all

of clox, by far. When the interpreter executes a user’s program, it will spend

something like 90% of its time inside run(). It is the beating heart of the

VM.

到目前为止,这是clox中最重要的一个函数。当解释器执行用户的程序时,它有大约90%的时间是在run()中。它是虚拟机跳动的心脏。

Despite that dramatic intro, it’s conceptually pretty simple. We have an outer loop that goes and goes. Each turn through that loop, we read and execute a single bytecode instruction. 尽管这个介绍很戏剧性,但从概念上来说很简单。我们有一个不断进行的外层循环。每次循环中,我们会读取并执行一条字节码指令。

To process an instruction, we first figure out what kind of instruction we’re

dealing with. The READ_BYTE macro reads the byte currently pointed at by ip

and then advances the instruction pointer. The first

byte of any instruction is the opcode. Given a numeric opcode, we need to get to

the right C code that implements that instruction’s semantics. This process is

called decoding or dispatching the instruction.

为了处理一条指令,我们首先需要弄清楚要处理的是哪种指令。READ_BYTE这个宏会读取ip当前指向字节,然后推进指令指针。任何指令的第一个字节都是操作码。给定一个操作码,我们需要找到实现该指令语义的正确的C代码。这个过程被称为解码或指令分派。

We do that process for every single instruction, every single time one is executed, so this is the most performance critical part of the entire virtual machine. Programming language lore is filled with clever techniques to do bytecode dispatch efficiently, going all the way back to the early days of computers. 每一条指令,每一次执行时,我们都会进行这个过程,所以这是整个虚拟机性能最关键的部分。编程语言的传说中充满了高效进行字节码分派的各种奇技淫巧,一直可以追溯到计算机的早期。

Alas, the fastest solutions require either non-standard extensions to C, or

handwritten assembly code. For clox, we’ll keep it simple. Just like our

disassembler, we have a single giant switch statement with a case for each

opcode. The body of each case implements that opcode’s behavior.

可惜的是,最快的解决方案要么需要对C进行非标准的扩展,要么需要手写汇编代码。对于clox,我们要保持简单。就像我们的反汇编程序一样,我们写一个巨大的switch语句,其中每个case对应一个操作码。每个case代码体实现了操作码的行为。

So far, we handle only a single instruction, OP_RETURN, and the only thing it

does is exit the loop entirely. Eventually, that instruction will be used to

return from the current Lox function, but we don’t have functions yet, so we’ll

repurpose it temporarily to end the execution.

到目前为止,我们只处理了一条指令,OP_RETURN,而它做的唯一的事情就是完全退出循环。最终,该指令将被用于从当前的Lox函数返回,但是我们目前还没有函数,所以我们暂时用它来结束代码执行。

Let’s go ahead and support our one other instruction. 让我们继续支持另一个指令。

switch (instruction = READ_BYTE()) {

in run()

case OP_CONSTANT: { Value constant = READ_CONSTANT(); printValue(constant); printf("\n"); break; }

case OP_RETURN: {

We don’t have enough machinery in place yet to do anything useful with a

constant. For now, we’ll just print it out so we interpreter hackers can see

what’s going on inside our VM. That call to printf() necessitates an include.

我们还没有足够的机制来使用常量做任何有用的事。现在,我们只是把它打印出来,这样我们这些解释器黑客就可以看到我们的VM内部发生了什么。调用printf()方法需要进行include。

add to top of file

#include <stdio.h>

#include "common.h"

We also have a new macro to define. 我们还需要定义一个新的宏。

#define READ_BYTE() (*vm.ip++)

in run()

#define READ_CONSTANT() (vm.chunk->constants.values[READ_BYTE()])

for (;;) {

READ_CONSTANT() reads the next byte from the bytecode, treats the resulting

number as an index, and looks up the corresponding Value in the chunk’s constant

table. In later chapters, we’ll add a few more instructions with operands that

refer to constants, so we’re setting up this helper macro now.

READ_CONTANT()从字节码中读取下一个字节,将得到的数字作为索引,并在代码块的常量表中查找相应的Value。在后面的章节中,我们将添加一些操作数指向常量的指令,所以我们现在要设置这个辅助宏。

Like the previous READ_BYTE macro, READ_CONSTANT is only used inside

run(). To make that scoping more explicit, the macro definitions themselves

are confined to that function. We define them at the

beginning and—because we care—undefine them at the end.

与之前的READ_BYTE宏类似,READ_CONSTANT只会在run()方法中使用。为了使作用域更明确,宏定义本身要被限制在该函数中。我们在开始时定义了它们,然后因为我们比较关心,在结束时取消它们的定义。

#undef READ_BYTE

in run()

#undef READ_CONSTANT

}

15 . 1 . 2执行跟踪

If you run clox now, it executes the chunk we hand-authored in the last chapter

and spits out 1.2 to your terminal. We can see that it’s working, but that’s

only because our implementation of OP_CONSTANT has temporary code to log the

value. Once that instruction is doing what it’s supposed to do and plumbing that

constant along to other operations that want to consume it, the VM will become a

black box. That makes our lives as VM implementers harder.

如果现在运行clox,它会执行我们在上一章中手工编写的字节码块,并向终端输出1.2。我们可以看到它在工作,但这是因为我们在OP_CONSTANT的实现中,使用临时代码记录了这个值。一旦该指令执行了它应做的操作,并将取得的常量传递给其它想要使用该常量的操作,虚拟机就会变成一个黑盒子。这使得我们作为虚拟机实现者的工作更加艰难。

To help ourselves out, now is a good time to add some diagnostic logging to the VM like we did with chunks themselves. In fact, we’ll even reuse the same code. We don’t want this logging enabled all the time—it’s just for us VM hackers, not Lox users—so first we create a flag to hide it behind. 为了帮助我们自己解脱这种困境,现在是给虚拟机添加一些诊断性日志的好时机,就像我们对代码块本身所做的那样。事实上,我们甚至会重用相同的代码。我们不希望一直启用这个日志—它只针对我们这些虚拟机开发者,而不是Lox用户—所以我们首先创建一个标志来隐藏它。

#include <stdint.h>

#define DEBUG_TRACE_EXECUTION

#endif

When this flag is defined, the VM disassembles and prints each instruction right before executing it. Where our previous disassembler walked an entire chunk once, statically, this disassembles instructions dynamically, on the fly. 定义了这个标志之后,虚拟机在执行每条指令之前都会反汇编并将其打印出来。我们之前的反汇编程序只是静态地遍历一次整个字节码块,而这个反编译程序则是动态地、即时地对指令进行反汇编。

for (;;) {

in run()

#ifdef DEBUG_TRACE_EXECUTION disassembleInstruction(vm.chunk, (int)(vm.ip - vm.chunk->code)); #endif

uint8_t instruction;

Since disassembleInstruction() takes an integer byte offset and we store the

current instruction reference as a direct pointer, we first do a little pointer

math to convert ip back to a relative offset from the beginning of the

bytecode. Then we disassemble the instruction that begins at that byte.

由于 disassembleInstruction() 方法接收一个整数offset作为字节偏移量,而我们将当前指令引用存储为一个直接指针,所以我们首先要做一个小小的指针运算,将ip转换成从字节码开始的相对偏移量。然后,我们对从该字节开始的指令进行反汇编。

As ever, we need to bring in the declaration of the function before we can call it. 跟之前一样,我们需要在调用函数之前先引入函数的声明。

#include "common.h"

#include "debug.h"

#include "vm.h"

I know this code isn’t super impressive so far—it’s literally a switch

statement wrapped in a for loop but, believe it or not, this is one of the two

major components of our VM. With this, we can imperatively execute instructions.

Its simplicity is a virtue—the less work it does, the faster it can do it.

Contrast this with all of the complexity and overhead we had in jlox with the

Visitor pattern for walking the AST.

我知道这段代码到目前为止还不是很令人印象深刻—它实际上只是一个封装在for循环中的switch语句,但信不信由你,这就是我们虚拟机的两个主要组成部分之一。有了它,我们就可以命令式地执行指令。它的简单是一种优点—它做的工作越少,就能做得越快。作为对照,可以回想一下我们在jlox中使用Visitor模式遍历AST的复杂度和开销。

15 . 2一个值栈操作器

In addition to imperative side effects, Lox has expressions that produce, modify, and consume values. Thus, our compiled bytecode needs a way to shuttle values around between the different instructions that need them. For example: 除了命令式的副作用外,Lox还有产生、修改和使用值的表达式。因此,我们编译的字节码还需要一种方法在需要值的不同指令之间传递它们。例如:

print 3 - 2;

We obviously need instructions for the constants 3 and 2, the print statement,

and the subtraction. But how does the subtraction instruction know that 3 is

the minuend and 2 is the subtrahend? How does the print

instruction know to print the result of that?

显然我们需要常数3和2、print语句和减法对应的指令。但是减法指令如何知道3是被减数而2是减数呢?打印指令怎么知道要打印计算结果的呢?

To put a finer point on it, look at this thing right here: 为了说得更清楚一点,看看下面的代码:

fun echo(n) { print n; return n; } print echo(echo(1) + echo(2)) + echo(echo(4) + echo(5));

I wrapped each subexpression in a call to echo() that prints and returns its

argument. That side effect means we can see the exact order of operations.

我将每个子表达都包装在对echo()的调用中,这个调用会打印并返回其参数。这个副作用意味着我们可以看到操作的确切顺序。

Don’t worry about the VM for a minute. Think about just the semantics of Lox

itself. The operands to an arithmetic operator obviously need to be evaluated

before we can perform the operation itself. (It’s pretty hard to add a + b if

you don’t know what a and b are.) Also, when we implemented expressions in

jlox, we decided that the left operand must be

evaluated before the right.

暂时不要担心虚拟机的问题。只考虑Lox本身的语义。算术运算符的操作数显然需要在执行运算操作之前求值(如果你不知道a和b是什么,就很难计算a+b)。另外,当我们在jlox中实现表达式时,我们决定了左操作数必须在右操作数之前进行求值。

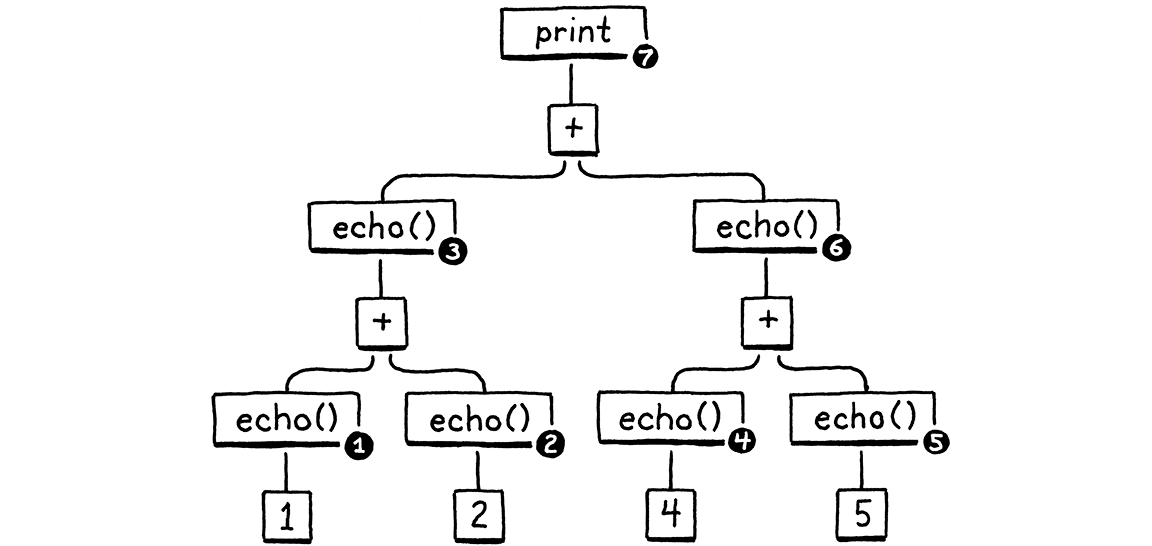

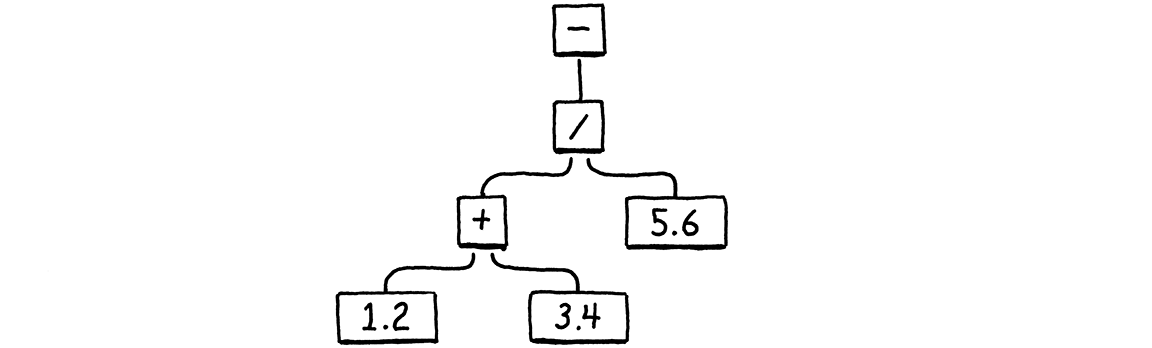

Here is the syntax tree for the print statement:

下面是print语句的语法树:

Given left-to-right evaluation, and the way the expressions are nested, any correct Lox implementation must print these numbers in this order: 确定了从左到右的求值顺序,以及表达式嵌套方式,任何一个正确的Lox实现都 必须 按照下面的顺序打印这些数字:

1 // from echo(1) 2 // from echo(2) 3 // from echo(1 + 2) 4 // from echo(4) 5 // from echo(5) 9 // from echo(4 + 5) 12 // from print 3 + 9

Our old jlox interpreter accomplishes this by recursively traversing the AST. It does a postorder traversal. First it recurses down the left operand branch, then the right operand, then finally it evaluates the node itself. 我们的老式jlox解释器通过递归遍历AST来实现这一点。其中使用的是后序遍历。首先,它向下递归左操作数分支,然后是右操作数分支,最后计算节点本身。

After evaluating the left operand, jlox needs to store that result somewhere temporarily while it’s busy traversing down through the right operand tree. We use a local variable in Java for that. Our recursive tree-walk interpreter creates a unique Java call frame for each node being evaluated, so we could have as many of these local variables as we needed. 在对左操作数求值之后,jlox需要将结果临时保存在某个地方,然后再向下遍历右操作数。我们使用Java中的一个局部变量来实现。我们的递归树遍历解释器会为每个正在求值的节点创建一个单独的Java调用帧,所以我们可以根据需要维护很多这样的局部变量。

In clox, our run() function is not recursive—the nested expression tree is

flattened out into a linear series of instructions. We don’t have the luxury of

using C local variables, so how and where should we store these temporary

values? You can probably guess already, but I want to

really drill into this because it’s an aspect of programming that we take for

granted, but we rarely learn why computers are architected this way.

在clox中,我们的run()函数不是递归的—嵌套的表达式被展开成一系列线性指令。我们没有办法使用C语言的局部变量,那我们应该如何存储这些临时值呢?你可能已经猜到了,但我想真正深入研究这个问题,因为这是编程中我们习以为常的一个方面,但我们很少了解为什么计算机是这样架构的。

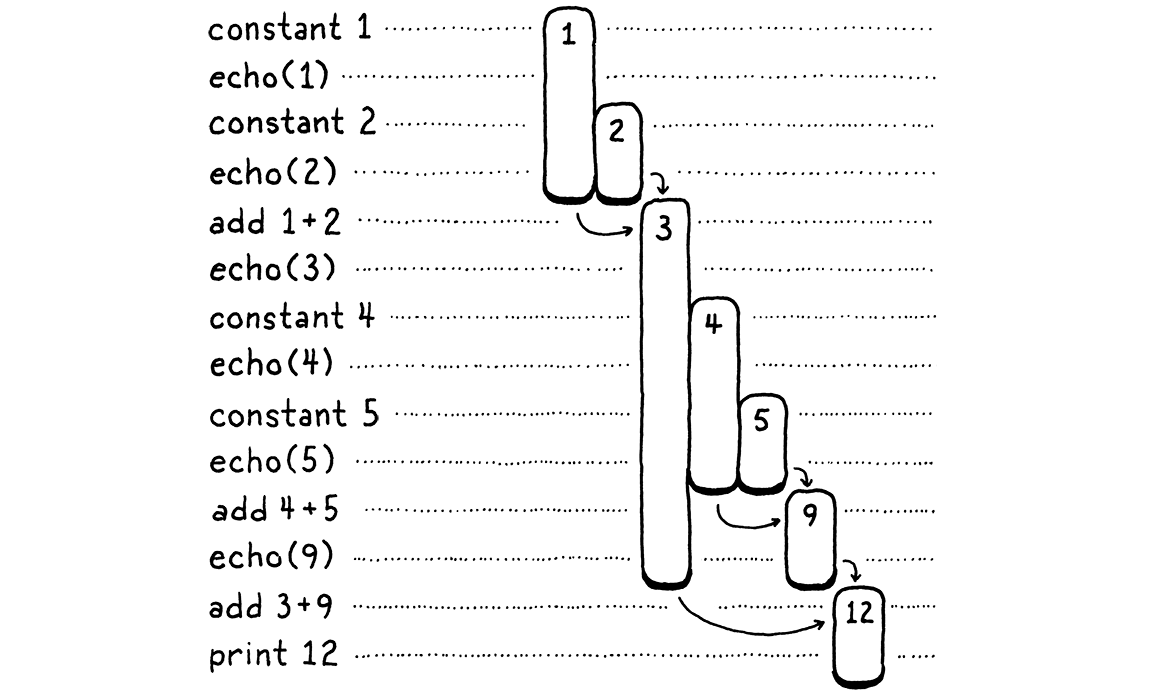

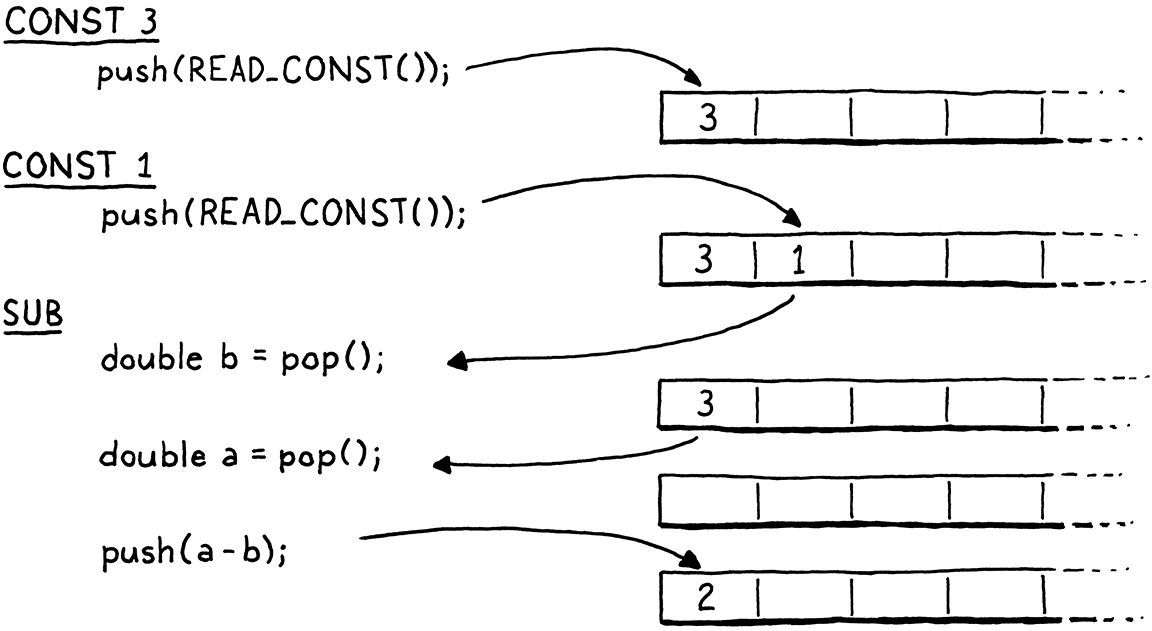

Let’s do a weird exercise. We’ll walk through the execution of the above program a step at a time: 让我们做一个奇怪的练习。我们来一步一步地遍历上述程序的执行过程:

On the left are the steps of code. On the right are the values we’re tracking. Each bar represents a number. It starts when the value is first produced—either a constant or the result of an addition. The length of the bar tracks when a previously produced value needs to be kept around, and it ends when that value finally gets consumed by an operation. 左边是代码的执行步骤。右边是我们要追踪的值。每条杠代表一个数字。起点是数值产生时—要么是一个常数,要么是一个加法计算结果;杠的长度表示之前产生的值需要保留的时间;当该值最终被某个操作消费后,杠就到终点了。

As you step through, you see values appear and then later get eaten. The longest-lived ones are the values produced from the left-hand side of an addition. Those stick around while we work through the right-hand operand expression. 随着你不断执行,你会看到一些数值出现,然后被消费掉。寿命最长的是加法左侧产生的值。当我们在处理右边的操作数表达式时,这些值会一直存在。

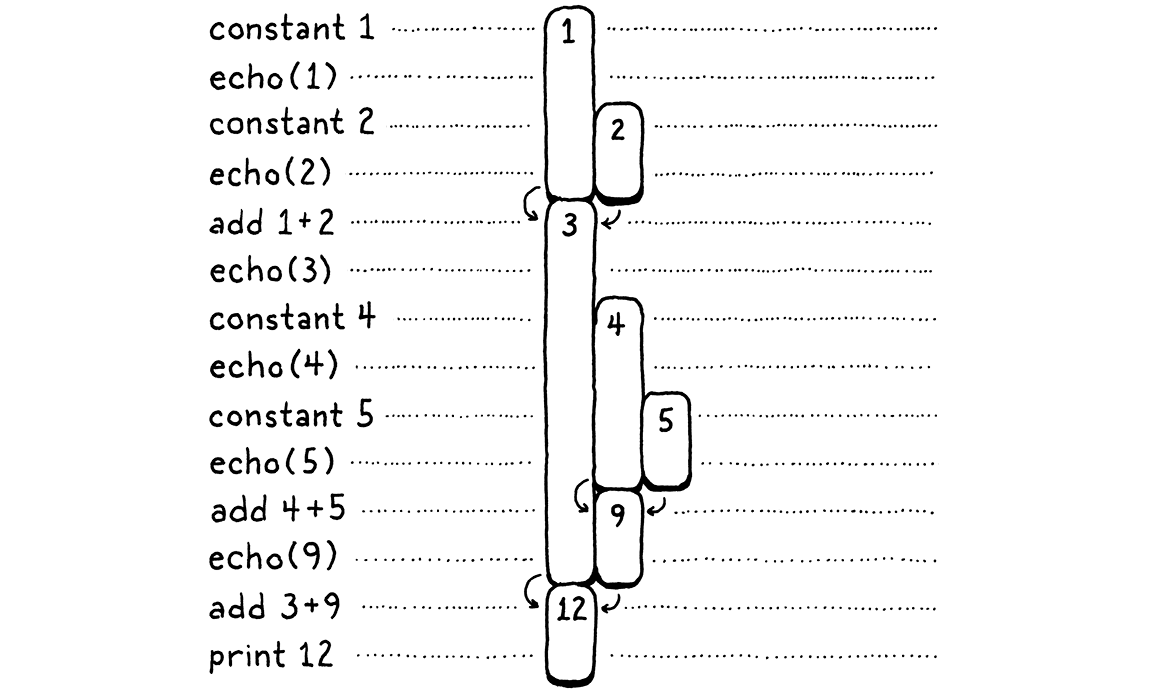

In the above diagram, I gave each unique number its own visual column. Let’s be a little more parsimonious. Once a number is consumed, we allow its column to be reused for another later value. In other words, we take all of those gaps up there and fill them in, pushing in numbers from the right: 在上图中,我为每个数字提供了单独的可视化列。让我们更简洁一些。一旦一个数字被消费了,我们就允许它的列被其它值重用。换句话说,我们将数字从右向左推入,把上面的空隙都填上:

There’s some interesting stuff going on here. When we shift everything over, each number still manages to stay in a single column for its entire life. Also, there are no gaps left. In other words, whenever a number appears earlier than another, then it will live at least as long as that second one. The first number to appear is the last to be consumed. Hmm . . . last-in, first-out . . . why, that’s a stack! 这里有一些有趣的事情发生了。当我们把所有数字都移动以后,每个数字在整个生命周期中仍然能保持在一列。此外,也没有留下任何空隙。换句话说,只要一个数字比另一个数字出现得早,那么它的寿命至少和第二个数字一样长。第一个出现的数字是最后一个消费掉的,嗯……后进先出……哎呀,这是一个栈!

In the second diagram, each time we introduce a number, we push it onto the stack from the right. When numbers are consumed, they are always popped off from rightmost to left. 在第二张图中,每次我们生成一个数字时,都会从右边将它压入栈。当数字被消费时,它们也是从右向左进行弹出。

Since the temporary values we need to track naturally have stack-like behavior, our VM will use a stack to manage them. When an instruction “produces” a value, it pushes it onto the stack. When it needs to consume one or more values, it gets them by popping them off the stack. 由于我们需要跟踪的临时值天然具有类似栈的行为,我们的虚拟机将使用栈来管理它们。当一条指令“生成”一个值时,它会把这个值压入栈中。当它需要消费一个或多个值时,通过从栈中弹出数据来获得这些值。

15 . 2 . 1虚拟机的栈

Maybe this doesn’t seem like a revelation, but I love stack-based VMs. When you first see a magic trick, it feels like something actually magical. But then you learn how it works—usually some mechanical gimmick or misdirection—and the sense of wonder evaporates. There are a couple of ideas in computer science where even after I pulled them apart and learned all the ins and outs, some of the initial sparkle remained. Stack-based VMs are one of those. 也许这看起来不像是什么新发现,但我喜欢基于栈的虚拟机。当你第一次看到一个魔术时,你会觉得它真的很神奇。但是当你了解到它是如何工作的—通常是一些机械式花招或误导—惊奇的感觉就消失了。在计算机科学中,有一些理念,即使我把它们拆开并了解了所有的来龙去脉之后,最初的闪光点仍然存在。基于堆栈的虚拟机就是其中之一。

As you’ll see in this chapter, executing instructions in a stack-based VM is dead simple. In later chapters, you’ll also discover that compiling a source language to a stack-based instruction set is a piece of cake. And yet, this architecture is fast enough to be used by production language implementations. It almost feels like cheating at the programming language game. 你在本章中将会看到,在基于堆栈的虚拟机中执行指令是非常简单的。在后面的章节中,你还会发现,将源语言编译成基于栈的指令集是小菜一碟。但是,这种架构的速度快到足以在产生式语言的实现中使用。这感觉就像是在编程语言游戏中作弊。

Alrighty, it’s codin’ time! Here’s the stack: 好了,编码时间到!下面是栈:

typedef struct {

Chunk* chunk;

uint8_t* ip;

in struct VM

Value stack[STACK_MAX]; Value* stackTop;

} VM;

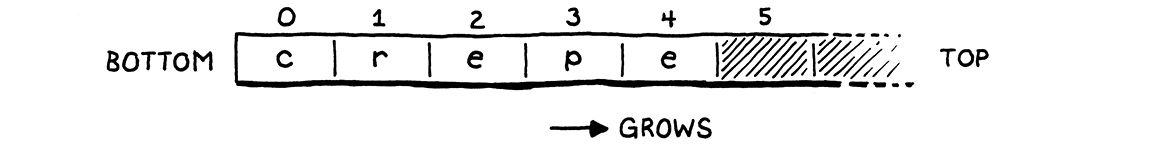

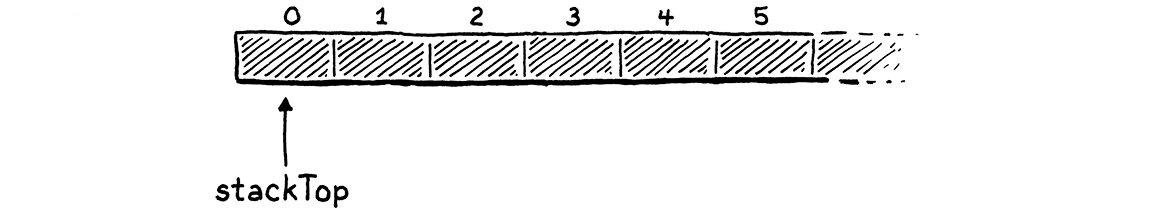

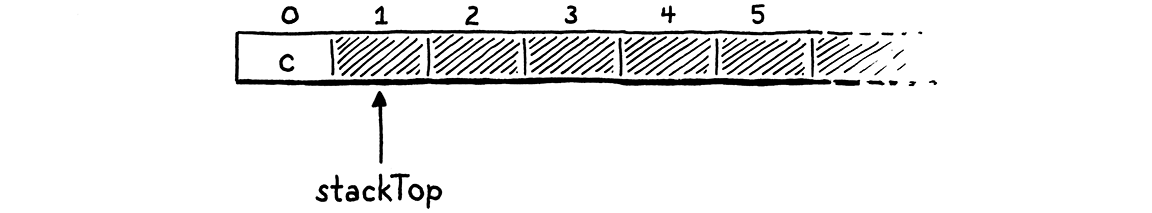

We implement the stack semantics ourselves on top of a raw C array. The bottom of the stack—the first value pushed and the last to be popped—is at element zero in the array, and later pushed values follow it. If we push the letters of “crepe”—my favorite stackable breakfast item—onto the stack, in order, the resulting C array looks like this: 我们在一个原生的C数组上自己实现了栈语义。栈的底部—第一个推入的值和最后一个被弹出的值—位于数组中的零号位置,后面推入的值跟在它后面。如果我们把“crepe”几个字母按顺序推入栈中,得到的C数组看起来像这样:

Since the stack grows and shrinks as values are pushed and popped, we need to

track where the top of the stack is in the array. As with ip, we use a direct

pointer instead of an integer index since it’s faster to dereference the pointer

than calculate the offset from the index each time we need it.

由于栈会随着值的压入和弹出而伸缩,我们需要跟踪栈的顶部在数组中的位置。和ip一样,我们使用一个直接指针而不是整数索引,因为每次我们需要使用它时,解引用比计算索引的偏移量更快。

The pointer points at the array element just past the element containing the top value on the stack. That seems a little odd, but almost every implementation does this. It means we can indicate that the stack is empty by pointing at element zero in the array. 指针指向数组中栈顶元素的下一个元素位置,这看起来有点奇怪,但几乎每个实现都会这样做。这意味着我们可以通过指向数组中的零号元素来表示栈是空的。

If we pointed to the top element, then for an empty stack we’d need to point at element -1. That’s undefined in C. As we push values onto the stack . . . 如果我们指向栈顶元素,那么对于空栈,我们就需要指向-1位置的元素。这在C语言中是没有定义的。当我们把值压入栈时:

. . . stackTop always points just past the last item.

stackTop一直会超过栈中的最后一个元素。

I remember it like this: stackTop points to where the next value to be pushed

will go. The maximum number of values we can store on the stack (for now, at

least) is:

我是这样记的:stackTop指向下一个值要被压入的位置。我们在栈中可以存储的值的最大数量(至少目前是这样)为:

#include "chunk.h"

#define STACK_MAX 256

typedef struct {

Giving our VM a fixed stack size means it’s possible for some sequence of instructions to push too many values and run out of stack space—the classic “stack overflow”. We could grow the stack dynamically as needed, but for now we’ll keep it simple. Since VM uses Value, we need to include its declaration. 给我们的虚拟机一个固定的栈大小,意味着某些指令系列可能会压入太多的值并耗尽栈空间—典型的“堆栈溢出”。我们可以根据需要动态地增加栈,但是现在我们还是保持简单。因为VM中会使用Value,我们需要包含它的声明。

#include "chunk.h"

#include "value.h"

#define STACK_MAX 256

Now that VM has some interesting state, we get to initialize it. 现在,虚拟机中有了一些有趣的状态,我们要对它进行初始化。

void initVM() {

in initVM()

resetStack();

}

That uses this helper function: 其中使用了这个辅助函数:

add after variable vm

static void resetStack() { vm.stackTop = vm.stack; }

Since the stack array is declared directly inline in the VM struct, we don’t

need to allocate it. We don’t even need to clear the unused cells in the

array—we simply won’t access them until after values have been stored in

them. The only initialization we need is to set stackTop to point to the

beginning of the array to indicate that the stack is empty.

因为栈数组是直接在VM结构体中内联声明的,所以我们不需要为其分配空间。我们甚至不需要清除数组中不使用的单元—我们只有在值存入之后才会访问它们。我们需要的唯一的初始化操作就是将stackTop指向数组的起始位置,以表明栈是空的。

The stack protocol supports two operations: 栈协议支持两种操作:

InterpretResult interpret(Chunk* chunk);

add after interpret()

void push(Value value); Value pop();

#endif

You can push a new value onto the top of the stack, and you can pop the most recently pushed value back off. Here’s the first function: 你可以把一个新值压入栈顶,你也可以把最近压入的值弹出。下面是第一个函数:

add after freeVM()

void push(Value value) { *vm.stackTop = value; vm.stackTop++; }

If you’re rusty on your C pointer syntax and operations, this is a good warm-up.

The first line stores value in the array element at the top of the stack.

Remember, stackTop points just past the last used element, at the next

available one. This stores the value in that slot. Then we increment the pointer

itself to point to the next unused slot in the array now that the previous slot

is occupied.

如果你对C指针的语法和操作感到生疏,这是一个很好的熟悉的机会。第一行在栈顶的数组元素中存储value。记住,stackTop刚刚跳过上次使用的元素,即下一个可用的元素。这里把值存储在该元素槽中。接着,因为上一个槽被占用了,我们增加指针本身,指向数组中下一个未使用的槽。

Popping is the mirror image. 弹出正好是压入的镜像操作。

add after push()

Value pop() { vm.stackTop--; return *vm.stackTop; }

First, we move the stack pointer back to get to the most recent used slot in

the array. Then we look up the value at that index and return it. We don’t need

to explicitly “remove” it from the array—moving stackTop down is enough to

mark that slot as no longer in use.

首先,我们将栈指针回退到数组中最近使用的槽。然后,我们查找该索引处的值并将其返回。我们不需要显式地将其从数组中“移除”—将stackTop下移就足以将该槽标记为不再使用了。

15 . 2 . 2栈跟踪

We have a working stack, but it’s hard to see that it’s working. When we start implementing more complex instructions and compiling and running larger pieces of code, we’ll end up with a lot of values crammed into that array. It would make our lives as VM hackers easier if we had some visibility into the stack. 我们有了一个工作的栈,但是很难看出它在工作。当我们开始实现更复杂的指令,编译和运行更大的代码片段时,最终会在这个数组中塞入很多值。如果我们对栈有一定的可见性,那么作为虚拟机开发者,我们就会更轻松。

To that end, whenever we’re tracing execution, we’ll also show the current contents of the stack before we interpret each instruction. 为此,每当我们追踪执行情况时,我们也会在解释每条指令之前展示栈中的当前内容。

#ifdef DEBUG_TRACE_EXECUTION

in run()

printf(" "); for (Value* slot = vm.stack; slot < vm.stackTop; slot++) { printf("[ "); printValue(*slot); printf(" ]"); } printf("\n");

disassembleInstruction(vm.chunk,

We loop, printing each value in the array, starting at the first (bottom of the stack) and ending when we reach the top. This lets us observe the effect of each instruction on the stack. The output is pretty verbose, but it’s useful when we’re surgically extracting a nasty bug from the bowels of the interpreter. 我们循环打印数组中的每个值,从第一个值开始(栈底),到栈顶结束。这样我们可以观察到每条指令对栈的影响。这个输出会相当冗长,但是从我们在解释器中遇到令人讨厌的错误时,这就会很有用了。

Stack in hand, let’s revisit our two instructions. First up: 堆栈在手,让我们重新审视一下目前的两条指令。首先是:

case OP_CONSTANT: {

Value constant = READ_CONSTANT();

in run()

replace 2 lines

push(constant);

break;

In the last chapter, I was hand-wavey about how the OP_CONSTANT instruction

“loads” a constant. Now that we have a stack you know what it means to actually

produce a value: it gets pushed onto the stack.

在上一节中,我粗略介绍了OP_CONSTANT指令是如何“加载”一个常量的。现在我们有了一个堆栈,你就知道产生一个值实际上意味着什么:将它压入栈。

case OP_RETURN: {

in run()

printValue(pop()); printf("\n");

return INTERPRET_OK;

Then we make OP_RETURN pop the stack and print the top value before exiting.

When we add support for real functions to clox, we’ll change this code. But, for

now, it gives us a way to get the VM executing simple instruction sequences and

displaying the result.

接下来,我们让OP_RETURN在退出之前弹出栈顶值并打印。等到我们在clox中添加对真正的函数的支持时,我们将会修改这段代码。但是,目前来看,我们可以使用这种方法让VM执行简单的指令序列并显示结果。

15 . 3数学计算器

The heart and soul of our VM are in place now. The bytecode loop dispatches and executes instructions. The stack grows and shrinks as values flow through it. The two halves work, but it’s hard to get a feel for how cleverly they interact with only the two rudimentary instructions we have so far. So let’s teach our interpreter to do arithmetic. 我们的虚拟机的核心和灵魂现在都已经就位了。字节码循环分派和执行指令。栈堆随着数值的流动而增长和收缩。这两部分都在工作,但仅凭我们目前的两条基本指令,很难感受到它们如何巧妙地互动。所以让我们教解释器如何做算术。

We’ll start with the simplest arithmetic operation, unary negation. 我们从最简单的算术运算开始,即一元取负。

var a = 1.2; print -a; // -1.2.

The prefix - operator takes one operand, the value to negate. It produces a

single result. We aren’t fussing with a parser yet, but we can add the

bytecode instruction that the above syntax will compile to.

前缀的-运算符接受一个操作数,也就是要取负的值。它只产生一个结果。我们还没有对解析器进行处理,但可以添加上述语法编译后对应的字节码指令。

OP_CONSTANT,

in enum OpCode

OP_NEGATE,

OP_RETURN,

We execute it like so: 我们这样执行它:

}

in run()

case OP_NEGATE: push(-pop()); break;

case OP_RETURN: {

The instruction needs a value to operate on, which it gets by popping from the stack. It negates that, then pushes the result back on for later instructions to use. Doesn’t get much easier than that. We can disassemble it too. 该指令需要操作一个值,该值通过弹出栈获得。它对该值取负,然后把结果重新压入栈,以便后面的指令使用。没有什么比这更简单的了。我们也可以对其反汇编:

case OP_CONSTANT:

return constantInstruction("OP_CONSTANT", chunk, offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_NEGATE: return simpleInstruction("OP_NEGATE", offset);

case OP_RETURN:

And we can try it out in our test chunk. 我们可以在测试代码中试一试。

writeChunk(&chunk, constant, 123);

in main()

writeChunk(&chunk, OP_NEGATE, 123);

writeChunk(&chunk, OP_RETURN, 123);

After loading the constant, but before returning, we execute the negate instruction. That replaces the constant on the stack with its negation. Then the return instruction prints that out: 在加载常量之后,返回之前,我们会执行取负指令。这条指令会将栈中的常量替换为其对应的负值。然后返回指令会打印出:

-1.2

Magical! 神奇!

15 . 3 . 1二元操作符

OK, unary operators aren’t that impressive. We still only ever have a single value on the stack. To really see some depth, we need binary operators. Lox has four binary arithmetic operators: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. We’ll go ahead and implement them all at the same time. 好吧,一元运算符并没有那么令人印象深刻。我们的栈中仍然只有一个值。要真正看到一些深度,我们需要二元运算符。Lox中有四个二进制算术运算符:加、减、乘、除。我们接下来会同时实现它们。

OP_CONSTANT,

in enum OpCode

OP_ADD, OP_SUBTRACT, OP_MULTIPLY, OP_DIVIDE,

OP_NEGATE,

Back in the bytecode loop, they are executed like this: 回到字节码循环中,它们是这样执行的:

}

in run()

case OP_ADD: BINARY_OP(+); break; case OP_SUBTRACT: BINARY_OP(-); break; case OP_MULTIPLY: BINARY_OP(*); break; case OP_DIVIDE: BINARY_OP(/); break;

case OP_NEGATE: push(-pop()); break;

The only difference between these four instructions is which underlying C operator they ultimately use to combine the two operands. Surrounding that core arithmetic expression is some boilerplate code to pull values off the stack and push the result. When we later add dynamic typing, that boilerplate will grow. To avoid repeating that code four times, I wrapped it up in a macro. 这四条指令之间唯一的区别是,它们最终使用哪一个底层C运算符来组合两个操作数。围绕这个核心算术表达式的是一些模板代码,用于从栈中获取数值,并将结果结果压入栈中。等我们后面添加动态类型时,这些模板代码会增加。为了避免这些代码重复出现四次,我将它包装在一个宏中。

#define READ_CONSTANT() (vm.chunk->constants.values[READ_BYTE()])

in run()

#define BINARY_OP(op) \ do { \ double b = pop(); \ double a = pop(); \ push(a op b); \ } while (false)

for (;;) {

I admit this is a fairly adventurous use of the C preprocessor. I hesitated to do this, but you’ll be glad in later chapters when we need to add the type checking for each operand and stuff. It would be a chore to walk you through the same code four times. 我承认这是对C预处理器的一次相当大胆的使用。我曾犹豫过要不要这么做,但在后面的章节中,等到我们需要为每个操作数和其它内容添加类型检查时,你就会高兴的。如果把相同的代码遍历四遍就太麻烦了。

If you aren’t familiar with the trick already, that outer do while loop

probably looks really weird. This macro needs to expand to a series of

statements. To be careful macro authors, we want to ensure those statements all

end up in the same scope when the macro is expanded. Imagine if you defined:

如果你对这个技巧还不熟悉,那么外层的do while循环可能看起来非常奇怪。这个宏需要扩展为一系列语句。作为一个谨慎的宏作者,我们要确保当宏展开时,这些语句都在同一个作用域内。想象一下,如果你定义了:

#define WAKE_UP() makeCoffee(); drinkCoffee();

And then used it like: 然后这样使用它:

if (morning) WAKE_UP();

The intent is to execute both statements of the macro body only if morning is

true. But it expands to:

其本意是在morning为true时执行这两个语句。但是宏展开结果为:

if (morning) makeCoffee(); drinkCoffee();;

Oops. The if attaches only to the first statement. You might think you could

fix this using a block.

哎呀。if只关联了第一条语句。您可能认为可以用代码块解决这个问题。

#define WAKE_UP() { makeCoffee(); drinkCoffee(); }

That’s better, but you still risk: 这样好一点,但还是有风险:

if (morning) WAKE_UP(); else sleepIn();

Now you get a compile error on the else because of that trailing ; after the

macro’s block. Using a do while loop in the macro looks funny, but it gives

you a way to contain multiple statements inside a block that also permits a

semicolon at the end.

现在你会在else子句遇到编译错误,因为在宏代码块后面有个;。在宏中使用do while循环看起来很滑稽,但它提供了一种方法,可以在一个代码块中包含多个语句,并且允许在末尾使用分号。

Where were we? Right, so what the body of that macro does is straightforward. A binary operator takes two operands, so it pops twice. It performs the operation on those two values and then pushes the result. 我们说到哪里了?对了,这个宏的主体所做的事情很直接。一个二元运算符接受两个操作数,因此会弹出栈两次,对这两个值执行操作,然后将结果压入栈。

Pay close attention to the order of the two pops. Note that we assign the

first popped operand to b, not a. It looks backwards. When the operands

themselves are calculated, the left is evaluated first, then the right. That

means the left operand gets pushed before the right operand. So the right

operand will be on top of the stack. Thus, the first value we pop is b.

请密切注意这两次弹出栈的顺序。注意,我们将第一个弹出的操作数赋值给b,而不是a。在对操作数求值时,先计算左操作数,再计算右操作数。这意味着左操作数会在右操作数之前被压入栈,所以右侧的操作数在栈顶。因此,我们弹出的第一个值属于b。

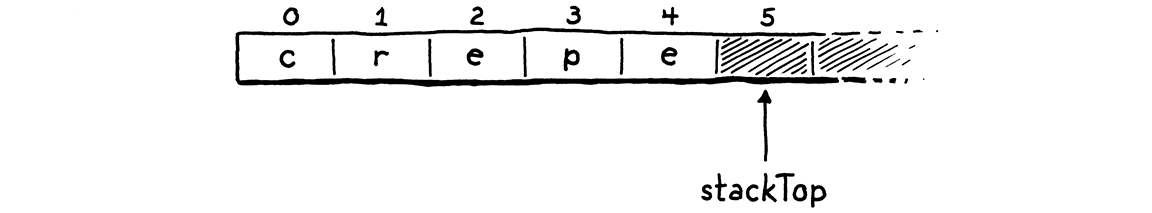

For example, if we compile 3 - 1, the data flow between the instructions looks

like so:

举例来说,如果我们编译3-1,指令之间的数据流看起来是这样的:

As we did with the other macros inside run(), we clean up after ourselves at

the end of the function.

正如我们在run()内的其它宏中做的那样,我们在函数结束时自行清理。

#undef READ_CONSTANT

in run()

#undef BINARY_OP

}

Last is disassembler support. 最后是反汇编器的支持。

case OP_CONSTANT:

return constantInstruction("OP_CONSTANT", chunk, offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_ADD: return simpleInstruction("OP_ADD", offset); case OP_SUBTRACT: return simpleInstruction("OP_SUBTRACT", offset); case OP_MULTIPLY: return simpleInstruction("OP_MULTIPLY", offset); case OP_DIVIDE: return simpleInstruction("OP_DIVIDE", offset);

case OP_NEGATE:

The arithmetic instruction formats are simple, like OP_RETURN. Even though the

arithmetic operators take operands—which are found on the stack—the

arithmetic bytecode instructions do not.

算术指令的格式很简单,类似于OP_RETURN。即使算术运算符需要操作数(从堆栈中获取),算术的 字节码指令 也不需要。

Let’s put some of our new instructions through their paces by evaluating a larger expression: 我们通过计算一个更大的表达式来检验一些新指令。

Building on our existing example chunk, here’s the additional instructions we need to hand-compile that AST to bytecode. 在我们现有的示例代码块基础上,下面是我们将AST手动编译为字节码后需要添加的指令。

int constant = addConstant(&chunk, 1.2); writeChunk(&chunk, OP_CONSTANT, 123); writeChunk(&chunk, constant, 123);

in main()

constant = addConstant(&chunk, 3.4); writeChunk(&chunk, OP_CONSTANT, 123); writeChunk(&chunk, constant, 123); writeChunk(&chunk, OP_ADD, 123); constant = addConstant(&chunk, 5.6); writeChunk(&chunk, OP_CONSTANT, 123); writeChunk(&chunk, constant, 123); writeChunk(&chunk, OP_DIVIDE, 123);

writeChunk(&chunk, OP_NEGATE, 123); writeChunk(&chunk, OP_RETURN, 123);

The addition goes first. The instruction for the left constant, 1.2, is already

there, so we add another for 3.4. Then we add those two using OP_ADD, leaving

it on the stack. That covers the left side of the division. Next we push the

5.6, and divide the result of the addition by it. Finally, we negate the result

of that.

首先进行加法运算。左边的常数1.2的指令已经存在了,所以我们再加一条3.4的指令。然后我们用OP_ADD把这两个值加起来,将结果压入堆栈中。这样就完成了除法的左操作数。接下来,我们压入5.6,并用加法的结果除以它。最后,我们对结果取负。

Note how the output of the OP_ADD implicitly flows into being an operand of

OP_DIVIDE without either instruction being directly coupled to each other.

That’s the magic of the stack. It lets us freely compose instructions without

them needing any complexity or awareness of the data flow. The stack acts like a

shared workspace that they all read from and write to.

注意,OP_ADD的输出如何隐式地变成了OP_DIVIDE的一个操作数,而这两条指令都没有直接耦合在一起。这就是堆栈的魔力。他让我们可以自由地编写指令,而无需任何复杂性或对于数据流的感知。堆栈就像一个共享工作区,它们都可以从中读取和写入。

In this tiny example chunk, the stack still only gets two values tall, but when we start compiling Lox source to bytecode, we’ll have chunks that use much more of the stack. In the meantime, try playing around with this hand-authored chunk to calculate different nested arithmetic expressions and see how values flow through the instructions and stack. 在这个小示例中,堆栈仍然只有两个值,但当我们开始将Lox源代码编译为字节码时,我们的代码块将使用更多的堆栈。同时,你可以试着用这个手工编写的字节码块来计算不同的嵌套算术表达式,看看数值是如何在指令和栈中流动的。

You may as well get it out of your system now. This is the last chunk we’ll build by hand. When we next revisit bytecode, we will be writing a compiler to generate it for us. 你不妨现在就把这块代码从系统中拿出来。这是我们手工构建的最后一个字节码块。当我们下次使用字节码时,我们将编写一个编译器来生成。

Challenges

-

What bytecode instruction sequences would you generate for the following expressions: 你会为以下表达式生成什么样的 字节码 指令序列:

1 * 2 + 3 1 + 2 * 3 3 - 2 - 1 1 + 2 * 3 - 4 / -5

(Remember that Lox does not have a syntax for negative number literals, so the

-5is negating the number 5.) (请记得,Lox语法中没有负数字面量,所以-5是对数字5取负) -

If we really wanted a minimal instruction set, we could eliminate either

OP_NEGATEorOP_SUBTRACT. Show the bytecode instruction sequence you would generate for: 如果我们真的想要一个最小指令集,我们可以取消OP_NEGATE或OP_SUBTRACT。请写出你为下面的表达式生成的字节码指令序列:4 - 3 * -2

First, without using

OP_NEGATE. Then, without usingOP_SUBTRACT. 首先是不能使用OP_NEGATE。然后,试一下不使用OP_SUBTRACT。Given the above, do you think it makes sense to have both instructions? Why or why not? Are there any other redundant instructions you would consider including? 综上所述,你认为同时拥有这两条指令有意义吗?为什么呢?还有没有其它指令可以考虑加入?

-

Our VM’s stack has a fixed size, and we don’t check if pushing a value overflows it. This means the wrong series of instructions could cause our interpreter to crash or go into undefined behavior. Avoid that by dynamically growing the stack as needed. 我们虚拟机的堆栈有一个固定大小,而且我们不会检查压入一个值是否会溢出。这意味着错误的指令序列可能会导致我们的解释器崩溃或进入未定义的行为。通过根据需求动态增长堆栈来避免这种情况。

What are the costs and benefits of doing so? 这样做的代价和好处是什么?

-

To interpret

OP_NEGATE, we pop the operand, negate the value, and then push the result. That’s a simple implementation, but it increments and decrementsstackTopunnecessarily, since the stack ends up the same height in the end. It might be faster to simply negate the value in place on the stack and leavestackTopalone. Try that and see if you can measure a performance difference. 为了解释OP_NEGATE,我们弹出操作数,对值取负,然后将结果压入栈。这是一个简单的实现,但它对stackTop进行了不必要的增减操作,因为栈最终的高度是相同的。简单地对栈中的值取负而不处理stackTop可能会更快。试一下,看看你是否能测出性能差异。Are there other instructions where you can do a similar optimization? 是否有其它指令可以做类似的优化?

Design Note: 基于寄存器的字节码

For the remainder of this book, we’ll meticulously implement an interpreter around a stack-based bytecode instruction set. There’s another family of bytecode architectures out there—register-based. Despite the name, these bytecode instructions aren’t quite as difficult to work with as the registers in an actual chip like x64. With real hardware registers, you usually have only a handful for the entire program, so you spend a lot of effort trying to use them efficiently and shuttling stuff in and out of them.

In a register-based VM, you still have a stack. Temporary values still get pushed onto it and popped when no longer needed. The main difference is that instructions can read their inputs from anywhere in the stack and can store their outputs into specific stack slots.

Take this little Lox script:

var a = 1; var b = 2; var c = a + b;

In our stack-based VM, the last statement will get compiled to something like:

load <a> // Read local variable a and push onto stack. load <b> // Read local variable b and push onto stack. add // Pop two values, add, push result. store <c> // Pop value and store in local variable c.

(Don’t worry if you don’t fully understand the load and store instructions yet. We’ll go over them in much greater detail when we implement variables.) We have four separate instructions. That means four times through the bytecode interpret loop, four instructions to decode and dispatch. It’s at least seven bytes of code—four for the opcodes and another three for the operands identifying which locals to load and store. Three pushes and three pops. A lot of work!

In a register-based instruction set, instructions can read from and store directly into local variables. The bytecode for the last statement above looks like:

add <a> <b> <c> // Read values from a and b, add, store in c.

The add instruction is bigger—it has three instruction operands that define

where in the stack it reads its inputs from and writes the result to. But since

local variables live on the stack, it can read directly from a and b and

then store the result right into c.

There’s only a single instruction to decode and dispatch, and the whole thing fits in four bytes. Decoding is more complex because of the additional operands, but it’s still a net win. There’s no pushing and popping or other stack manipulation.

The main implementation of Lua used to be stack-based. For Lua 5.0, the implementers switched to a register instruction set and noted a speed improvement. The amount of improvement, naturally, depends heavily on the details of the language semantics, specific instruction set, and compiler sophistication, but that should get your attention.

That raises the obvious question of why I’m going to spend the rest of the book doing a stack-based bytecode. Register VMs are neat, but they are quite a bit harder to write a compiler for. For what is likely to be your very first compiler, I wanted to stick with an instruction set that’s easy to generate and easy to execute. Stack-based bytecode is marvelously simple.

It’s also much better known in the literature and the community. Even though you may eventually move to something more advanced, it’s a good common ground to share with the rest of your language hacker peers.

在本书的其余部分,我们将围绕基于堆栈的字节码指令集精心实现一个解释器。此外还有另一种字节码架构—基于寄存器。尽管名称如此,但这些字节码指令并不像 x64 这样的真实芯片中的寄存器那样难以操作。对于真正的硬件寄存器,整个程序通常只用少数几个,所以你要花很多精力来有效地使用它们,并把数据存入或取出。(基于寄存器的字节码更接近于SPARC芯片支持的寄存器窗口)

在一个基于寄存器的虚拟机中,仍然有一个栈。临时值还是被压入栈中,当不再需要时再被弹出。主要的区别是,指令可以从栈的任意位置读取它们的输入值,并可以将它们的输出值存储到任一指定的槽中。

以Lox脚本为例:

var a = 1; var b = 2; var c = a + b;

在我们基于堆栈的虚拟机中,最后一条指令的编译结果类似于:

load <a> // 读取局部变量a,并将其压入栈 load <b> // 读取局部变量b,并将其压入栈 add // 弹出两个值,相加,将结果压入栈 store <c> // 弹出值,并存入局部变量c

(如果你还没有完全理解加载load和存储store指令,也不用担心。我们会在实现变量时详细地讨论它们)我们有四条独立的指令,这意味着会有四次字节码解释循环,四条指令需要解码和调度。这至少包含7个字节的代码—四个字节是操作码,另外三个是操作数,用于标识要加载和存储哪些局部变量。三次入栈,三次出栈,工作量很大!

在基于寄存器的指令集中,指令可以直接对局部变量进行读取和存储。上面最后一条语句的字节码如下所示:

add <a> <b> <c> // 从a和b中读取值,相加,并存储到c中

add指令比之前更大—有三个指令操作数,定义了从堆栈的哪个位置读取输入,并将结果写入哪个位置。但由于局部变量在堆栈中,它可以直接从a和b中读取数据,如何将结果存入c中。

只有一条指令需要解码和调度,整个程序只需要四个字节。由于有了额外的操作数,解码变得更加复杂,但相比之下它仍然是更优秀的。没有压入和弹出或其它堆栈操作。

Lua的实现曾经是基于堆栈的。到了Lua 5.0,实现切换到了寄存器指令集,并注意到速度有所提高。当然,提高的幅度很大程度上取决于语言语义的细节、特定指令集和编译器复杂性,但这应该引起你的注意。

这就引出了一个显而易见的问题:我为什么要在本书的剩余部分做一个基于堆栈的字节码。寄存器虚拟机是很好的,但要为它们编写编译器却相当困难。考虑到这可能是你写的第一个编译器,我想坚持使用一个易于生成和易于执行的指令集。基于堆栈的字节码是非常简单的。

它的文献和社区中也更广为人知。即使你最终可能会转向更高级的东西,这也是一个你可以与其他语言开发者分享的很好的共同点。