全局变量

If only there could be an invention that bottled up a memory, like scent. And it never faded, and it never got stale. And then, when one wanted it, the bottle could be uncorked, and it would be like living the moment all over again.

如果有一种发明能把一段记忆装进瓶子里就好了,像香味一样。它永远不会褪色,也不会变质。然后,当一个人想要的时候,可以打开瓶塞,就像重新活在那个时刻一样。

Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca 达芙妮-杜穆里埃, 蝴蝶梦

The previous chapter was a long exploration of one big, deep, fundamental computer science data structure. Heavy on theory and concept. There may have been some discussion of big-O notation and algorithms. This chapter has fewer intellectual pretensions. There are no large ideas to learn. Instead, it’s a handful of straightforward engineering tasks. Once we’ve completed them, our virtual machine will support variables. 上一章对一个大的、深入的、基本的计算机科学数据结构进行了长时间的探索。偏重理论和概念。可能有一些关于大O符号和算法的讨论。这一章没有那么多知识分子的自吹自擂。没有什么伟大的思想需要学习。相反,它是一些简单的工程任务。一旦我们完成了这些任务,我们的虚拟机就可以支持变量。

Actually, it will support only global variables. Locals are coming in the next chapter. In jlox, we managed to cram them both into a single chapter because we used the same implementation technique for all variables. We built a chain of environments, one for each scope, all the way up to the top. That was a simple, clean way to learn how to manage state. 事实上,它将只支持全局变量。局部变量将在下一章中支持。在jlox中,我们设法将它们塞进了一个章节,因为我们对所有变量都使用了相同的实现技术。我们建立了一个环境链,每个作用域都有一个,一直到顶部作用域。这是学习如何管理状态的一种简单、干净的方法。

But it’s also slow. Allocating a new hash table each time you enter a block or call a function is not the road to a fast VM. Given how much code is concerned with using variables, if variables go slow, everything goes slow. For clox, we’ll improve that by using a much more efficient strategy for local variables, but globals aren’t as easily optimized. 但它也很慢。每次进入一个代码块或调用一个函数时,都要分配一个新的哈希表,这不是通往快速虚拟机的道路。鉴于很多代码都与使用变量有关,如果变量操作缓慢,一切都会变慢。对于clox,我们会通过对局部变量使用更有效的策略来改善这一点,但全局变量不那么容易优化。

A quick refresher on Lox semantics: Global variables in Lox are “late bound”, or resolved dynamically. This means you can compile a chunk of code that refers to a global variable before it’s defined. As long as the code doesn’t execute before the definition happens, everything is fine. In practice, that means you can refer to later variables inside the body of functions. 快速复习一下Lox语义:Lox中的全局变量是“后期绑定”的,或者说是动态解析的。这意味着,你可以在全局变量被定义之前,编译引用它的一大块代码。只要代码在定义发生之前没有执行,就没有问题。在实践中,这意味着你可以在函数的主体中引用后面的变量。

fun showVariable() { print global; } var global = "after"; showVariable();

Code like this might seem odd, but it’s handy for defining mutually recursive functions. It also plays nicer with the REPL. You can write a little function in one line, then define the variable it uses in the next. 这样的代码可能看起来很奇怪,但它对于定义相互递归的函数很方便。它与REPL的配合也更好。你可以在一行中编写一个小函数,然后在下一行中定义它使用的变量。

Local variables work differently. Since a local variable’s declaration always occurs before it is used, the VM can resolve them at compile time, even in a simple single-pass compiler. That will let us use a smarter representation for locals. But that’s for the next chapter. Right now, let’s just worry about globals. 局部变量的工作方式不同。因为局部变量的声明总是发生在使用之前,虚拟机可以在编译时解析它们,即使是在简单的单遍编译器中。这让我们可以为局部变量使用更聪明的表示形式。但这是下一章的内容。现在,我们只考虑全局变量。

21 . 1语句

Variables come into being using variable declarations, which means now is also the time to add support for statements to our compiler. If you recall, Lox splits statements into two categories. “Declarations” are those statements that bind a new name to a value. The other kinds of statements—control flow, print, etc.—are just called “statements”. We disallow declarations directly inside control flow statements, like this: 变量是通过变量声明产生的,这意味着现在是时候向编译器中添加对语句的支持了。如果你还记得的话,Lox将语句分为两类。“声明”是那些将一个新名称与值绑定的语句。其它类型的语句—控制流、打印等—只被称为“语句”。我们不允许在控制流语句中直接使用声明,像这样:

if (monday) var croissant = "yes"; // Error.

Allowing it would raise confusing questions around the scope of the variable. So, like other languages, we prohibit it syntactically by having a separate grammar rule for the subset of statements that are allowed inside a control flow body. 允许这种做法会引发围绕变量作用域的令人困惑的问题。因此,像其它语言一样,对于允许出现在控制流主体内的语句子集,我们制定单独的语法规则,从而禁止这种做法。

statement → exprStmt | forStmt | ifStmt | printStmt | returnStmt | whileStmt | block ;

Then we use a separate rule for the top level of a script and inside a block. 然后,我们为脚本的顶层和代码块内部使用单独的规则。

declaration → classDecl | funDecl | varDecl | statement ;

The declaration rule contains the statements that declare names, and also

includes statement so that all statement types are allowed. Since block

itself is in statement, you can put declarations inside a control flow construct by nesting them inside a

block.

declaration包含声明名称的语句,也包含statement规则,这样所有的语句类型都是允许的。因为block本身就在statement中,你可以通过将声明嵌套在代码块中的方式将它们放在控制流结构中。

In this chapter, we’ll cover only a couple of statements and one declaration. 在本章中,我们只讨论几个语句和一个声明。

statement → exprStmt | printStmt ; declaration → varDecl | statement ;

Up to now, our VM considered a “program” to be a single expression since that’s all we could parse and compile. In a full Lox implementation, a program is a sequence of declarations. We’re ready to support that now. 到目前为止,我们的虚拟机都认为“程序”是一个表达式,因为我们只能解析和编译一条表达式。在完整的Lox实现中,程序是一连串的声明。我们现在已经准备要支持它了。

advance();

in compile()

replace 2 lines

while (!match(TOKEN_EOF)) { declaration(); }

endCompiler();

We keep compiling declarations until we hit the end of the source file. We compile a single declaration using this: 我们会一直编译声明语句,直到到达源文件的结尾。我们用这个方法来编译一条声明语句:

add after expression()

static void declaration() { statement(); }

We’ll get to variable declarations later in the chapter, so for now, we simply

forward to statement().

我们将在本章后面讨论变量声明,所以现在,我们直接使用statement()。

add after declaration()

static void statement() { if (match(TOKEN_PRINT)) { printStatement(); } }

Blocks can contain declarations, and control flow statements can contain other statements. That means these two functions will eventually be recursive. We may as well write out the forward declarations now. 代码块可以包含声明,而控制流语句可以包含其它语句。这意味着这两个函数最终是递归的。我们不妨现在就把前置声明写出来。

static void expression();

add after expression()

static void statement(); static void declaration();

static ParseRule* getRule(TokenType type);

21 . 1 . 1Print语句

We have two statement types to support in this chapter. Let’s start with print

statements, which begin, naturally enough, with a print token. We detect that

using this helper function:

在本章中,我们有两种语句类型需要支持。我们从print语句开始,它自然是以print标识开头的。我们使用这个辅助函数来检测:

add after consume()

static bool match(TokenType type) { if (!check(type)) return false; advance(); return true; }

You may recognize it from jlox. If the current token has the given type, we

consume the token and return true. Otherwise we leave the token alone and

return false. This helper function is implemented

in terms of this other helper:

你可能看出它是从jlox来的。如果当前的标识是指定类型,我们就消耗该标识并返回true。否则,我们就不处理该标识并返回false。这个辅助函数是通过另一个辅助函数实现的:

add after consume()

static bool check(TokenType type) { return parser.current.type == type; }

The check() function returns true if the current token has the given type.

It seems a little silly to wrap this in a function, but

we’ll use it more later, and I think short verb-named functions like this make

the parser easier to read.

如果当前标识符合给定的类型,check()函数返回true。将它封装在一个函数中似乎有点傻,但我们以后会更多地使用它,而且我们认为像这样简短的动词命名的函数使解析器更容易阅读。

If we did match the print token, then we compile the rest of the statement

here:

如果我们确实匹配到了print标识,那么我们在下面这个方法中编译该语句的剩余部分:

add after expression()

static void printStatement() { expression(); consume(TOKEN_SEMICOLON, "Expect ';' after value."); emitByte(OP_PRINT); }

A print statement evaluates an expression and prints the result, so we first

parse and compile that expression. The grammar expects a semicolon after that,

so we consume it. Finally, we emit a new instruction to print the result.

print语句会对表达式求值并打印出结果,所以我们首先解析并编译这个表达式。语法要求在表达式之后有一个分号,所以我们消耗一个分号标识。最后,我们生成一条新指令来打印结果。

OP_NEGATE,

in enum OpCode

OP_PRINT,

OP_RETURN,

At runtime, we execute this instruction like so: 在运行时,我们这样执行这条指令:

break;

in run()

case OP_PRINT: { printValue(pop()); printf("\n"); break; }

case OP_RETURN: {

When the interpreter reaches this instruction, it has already executed the code for the expression, leaving the result value on top of the stack. Now we simply pop and print it. 当解释器到达这条指令时,它已经执行了表达式的代码,将结果值留在了栈顶。现在我们只需要弹出该值并打印。

Note that we don’t push anything else after that. This is a key difference

between expressions and statements in the VM. Every bytecode instruction has a

stack effect that describes how the instruction

modifies the stack. For example, OP_ADD pops two values and pushes one,

leaving the stack one element smaller than before.

请注意,在此之后我们不会再向栈中压入任何内容。这是虚拟机中表达式和语句之间的一个关键区别。每个字节码指令都有堆栈效应,这个值用于描述指令如何修改堆栈内容。例如,OP_ADD会弹出两个值并压入一个值,使得栈中比之前少了一个元素。

You can sum the stack effects of a series of instructions to get their total effect. When you add the stack effects of the series of instructions compiled from any complete expression, it will total one. Each expression leaves one result value on the stack. 你可以把一系列指令的堆栈效应相加,得到它们的总体效应。如果把从任何一个完整的表达式中编译得到的一系列指令的堆栈效应相加,其总数是1。每个表达式会在栈中留下一个结果值。

The bytecode for an entire statement has a total stack effect of zero. Since a statement produces no values, it ultimately leaves the stack unchanged, though it of course uses the stack while it’s doing its thing. This is important because when we get to control flow and looping, a program might execute a long series of statements. If each statement grew or shrank the stack, it might eventually overflow or underflow. 整个语句对应字节码的总堆栈效应为0。因为语句不产生任何值,所以它最终会保持堆栈不变,尽管它在执行自己的操作时难免会使用堆栈。这一点很重要,因为等我们涉及到控制流和循环时,一个程序可能会执行一长串的语句。如果每条语句都增加或减少堆栈,最终就可能会溢出或下溢。

While we’re in the interpreter loop, we should delete a bit of code. 在解释器循环中,我们应该删除一些代码。

case OP_RETURN: {

in run()

replace 2 lines

// Exit interpreter.

return INTERPRET_OK;

When the VM only compiled and evaluated a single expression, we had some

temporary code in OP_RETURN to output the value. Now that we have statements

and print, we don’t need that anymore. We’re one step closer to the complete implementation of clox.

当虚拟机只编译和计算一条表达式时,我们在OP_RETURN中使用一些临时代码来输出值。现在我们已经有了语句和print,就不再需要这些了。我们离clox的完全实现又近了一步。

As usual, a new instruction needs support in the disassembler. 像往常一样,一条新指令需要反汇编程序的支持。

return simpleInstruction("OP_NEGATE", offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_PRINT: return simpleInstruction("OP_PRINT", offset);

case OP_RETURN:

That’s our print statement. If you want, give it a whirl:

这就是我们的print语句。如果你愿意,可以试一试:

print 1 + 2; print 3 * 4;

Exciting! OK, maybe not thrilling, but we can build scripts that contain as many statements as we want now, which feels like progress. 令人兴奋!好吧,也许没有那么激动人心,但是我们现在可以构建包含任意多语句的脚本,这感觉是一种进步。

21 . 1 . 2表达式语句

Wait until you see the next statement. If we don’t see a print keyword, then

we must be looking at an expression statement.

等待,直到你看到下一条语句。如果没有看到print关键字,那么我们看到的一定是一条表达式语句。

printStatement();

in statement()

} else { expressionStatement();

}

It’s parsed like so: 它是这样解析的:

add after expression()

static void expressionStatement() { expression(); consume(TOKEN_SEMICOLON, "Expect ';' after expression."); emitByte(OP_POP); }

An “expression statement” is simply an expression followed by a semicolon. They’re how you write an expression in a context where a statement is expected. Usually, it’s so that you can call a function or evaluate an assignment for its side effect, like this: “表达式语句”就是一个表达式后面跟着一个分号。这是在需要语句的上下文中写表达式的方式。通常来说,这样你就可以调用函数或执行赋值操作以触发其副作用,像这样:

brunch = "quiche"; eat(brunch);

Semantically, an expression statement evaluates the expression and discards the

result. The compiler directly encodes that behavior. It compiles the expression,

and then emits an OP_POP instruction.

从语义上说,表达式语句会对表达式求值并丢弃结果。编译器直接对这种行为进行编码。它会编译表达式,然后生成一条OP_POP指令。

OP_FALSE,

in enum OpCode

OP_POP,

OP_EQUAL,

As the name implies, that instruction pops the top value off the stack and forgets it. 顾名思义,该指令会弹出栈顶的值并将其遗弃。

case OP_FALSE: push(BOOL_VAL(false)); break;

in run()

case OP_POP: pop(); break;

case OP_EQUAL: {

We can disassemble it too. 我们也可以对它进行反汇编。

return simpleInstruction("OP_FALSE", offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_POP: return simpleInstruction("OP_POP", offset);

case OP_EQUAL:

Expression statements aren’t very useful yet since we can’t create any expressions that have side effects, but they’ll be essential when we add functions later. The majority of statements in real-world code in languages like C are expression statements. 表达式语句现在还不是很有用,因为我们无法创建任何有副作用的表达式,但等我们后面添加函数时,它们将是必不可少的。在像C这样的真正语言中,大部分语句都是表达式语句。

21 . 1 . 3错误同步

While we’re getting this initial work done in the compiler, we can tie off a loose end we left several chapters back. Like jlox, clox uses panic mode error recovery to minimize the number of cascaded compile errors that it reports. The compiler exits panic mode when it reaches a synchronization point. For Lox, we chose statement boundaries as that point. Now that we have statements, we can implement synchronization. 当我们在编译器中完成这些初始化工作时,我们可以把前几章遗留的一个小尾巴处理一下。与jlox一样,clox也使用了恐慌模式下的错误恢复来减少它所报告的级联编译错误。当编译器到达同步点时,就退出恐慌模式。对于Lox来说,我们选择语句边界作为同步点。现在我们有了语句,就可以实现同步了。

statement();

in declaration()

if (parser.panicMode) synchronize();

}

If we hit a compile error while parsing the previous statement, we enter panic mode. When that happens, after the statement we start synchronizing. 如果我们在解析前一条语句时遇到编译错误,我们就会进入恐慌模式。当这种情况发生时,我们会在这条语句之后开始同步。

add after printStatement()

static void synchronize() { parser.panicMode = false; while (parser.current.type != TOKEN_EOF) { if (parser.previous.type == TOKEN_SEMICOLON) return; switch (parser.current.type) { case TOKEN_CLASS: case TOKEN_FUN: case TOKEN_VAR: case TOKEN_FOR: case TOKEN_IF: case TOKEN_WHILE: case TOKEN_PRINT: case TOKEN_RETURN: return; default: ; // Do nothing. } advance(); } }

We skip tokens indiscriminately until we reach something that looks like a statement boundary. We recognize the boundary by looking for a preceding token that can end a statement, like a semicolon. Or we’ll look for a subsequent token that begins a statement, usually one of the control flow or declaration keywords. 我们会不分青红皂白地跳过标识,直到我们到达一个看起来像是语句边界的位置。我们识别边界的方式包括,查找可以结束一条语句的前驱标识,如分号;或者我们可以查找能够开始一条语句的后续标识,通常是控制流或声明语句的关键字之一。

21 . 2变量声明

Merely being able to print doesn’t win your language any prizes at the programming language fair, so let’s move on to something a little more ambitious and get variables going. There are three operations we need to support: 仅仅能够打印并不能为你的语言在编程语言博览会上赢得任何奖项,所以让我们继续做一些更有野心的事,让变量发挥作用。我们需要支持三种操作:

- Declaring a new variable using a

varstatement. 使用var语句声明一个新变量 - Accessing the value of a variable using an identifier expression. 使用标识符表达式访问一个变量的值

- Storing a new value in an existing variable using an assignment expression. 使用赋值表达式将一个新的值存储在现有的变量中

We can’t do either of the last two until we have some variables, so we start with declarations. 等我们有了变量以后,才能做后面两件事,所以我们从声明开始。

static void declaration() {

in declaration()

replace 1 line

if (match(TOKEN_VAR)) { varDeclaration(); } else { statement(); }

if (parser.panicMode) synchronize();

The placeholder parsing function we sketched out for the declaration grammar

rule has an actual production now. If we match a var token, we jump here:

我们为声明语法规则建立的占位解析函数现在已经有了实际的生成式。如果我们匹配到一个var标识,就跳转到这里:

add after expression()

static void varDeclaration() { uint8_t global = parseVariable("Expect variable name."); if (match(TOKEN_EQUAL)) { expression(); } else { emitByte(OP_NIL); } consume(TOKEN_SEMICOLON, "Expect ';' after variable declaration."); defineVariable(global); }

The keyword is followed by the variable name. That’s compiled by

parseVariable(), which we’ll get to in a second. Then we look for an =

followed by an initializer expression. If the user doesn’t initialize the

variable, the compiler implicitly initializes it to nil by emitting an OP_NIL instruction. Either way, we

expect the statement to be terminated with a semicolon.

关键字后面跟着变量名。它是由parseVariable()编译的,我们马上就会讲到。然后我们会寻找一个=,后跟初始化表达式。如果用户没有初始化变量,编译器会生成OP_NIL指令隐式地将其初始化为nil。无论哪种方式,我们都希望语句以分号结束。

There are two new functions here for working with variables and identifiers. Here is the first: 这里有两个新函数用于处理变量和标识符。下面是第一个:

static void parsePrecedence(Precedence precedence);

add after parsePrecedence()

static uint8_t parseVariable(const char* errorMessage) { consume(TOKEN_IDENTIFIER, errorMessage); return identifierConstant(&parser.previous); }

It requires the next token to be an identifier, which it consumes and sends here: 它要求下一个标识是一个标识符,它会消耗该标识并发送到这里:

static void parsePrecedence(Precedence precedence);

add after parsePrecedence()

static uint8_t identifierConstant(Token* name) { return makeConstant(OBJ_VAL(copyString(name->start, name->length))); }

This function takes the given token and adds its lexeme to the chunk’s constant table as a string. It then returns the index of that constant in the constant table. 这个函数接受给定的标识,并将其词素作为一个字符串添加到字节码块的常量表中。然后,它会返回该常量在常量表中的索引。

Global variables are looked up by name at runtime. That means the VM—the bytecode interpreter loop—needs access to the name. A whole string is too big to stuff into the bytecode stream as an operand. Instead, we store the string in the constant table and the instruction then refers to the name by its index in the table. 全局变量在运行时是按名称查找的。这意味着虚拟机(字节码解释器循环)需要访问该名称。整个字符串太大,不能作为操作数塞进字节码流中。相反,我们将字符串存储到常量表中,然后指令通过该名称在表中的索引来引用它。

This function returns that index all the way to varDeclaration() which later

hands it over to here:

这个函数会将索引一直返回给varDeclaration(),随后又将其传递到这里:

add after parseVariable()

static void defineVariable(uint8_t global) { emitBytes(OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL, global); }

This outputs the bytecode instruction that defines the new variable and stores its initial value. The index of the variable’s name in the constant table is the instruction’s operand. As usual in a stack-based VM, we emit this instruction last. At runtime, we execute the code for the variable’s initializer first. That leaves the value on the stack. Then this instruction takes that value and stores it away for later. 它会输出字节码指令,用于定义新变量并存储其初始化值。变量名在常量表中的索引是该指令的操作数。在基于堆栈的虚拟机中,我们通常是最后发出这条指令。在运行时,我们首先执行变量初始化器的代码,将值留在栈中。然后这条指令会获取该值并保存起来,以供日后使用。

Over in the runtime, we begin with this new instruction: 在运行时,我们从这条新指令开始:

OP_POP,

in enum OpCode

OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL,

OP_EQUAL,

Thanks to our handy-dandy hash table, the implementation isn’t too hard. 多亏了我们方便的哈希表,实现起来并不太难。

case OP_POP: pop(); break;

in run()

case OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL: { ObjString* name = READ_STRING(); tableSet(&vm.globals, name, peek(0)); pop(); break; }

case OP_EQUAL: {

We get the name of the variable from the constant table. Then we take the value from the top of the stack and store it in a hash table with that name as the key. 我们从常量表中获取变量的名称,然后我们从栈顶获取值,并以该名称为键将其存储在哈希表中。

This code doesn’t check to see if the key is already in the table. Lox is pretty lax with global variables and lets you redefine them without error. That’s useful in a REPL session, so the VM supports that by simply overwriting the value if the key happens to already be in the hash table. 这段代码并没有检查键是否已经在表中。Lox对全局变量的处理非常宽松,允许你重新定义它们而且不会出错。这在REPL会话中很有用,如果键恰好已经在哈希表中,虚拟机通过简单地覆盖值来支持这一点。

There’s another little helper macro: 还有另一个小的辅助宏:

#define READ_CONSTANT() (vm.chunk->constants.values[READ_BYTE()])

in run()

#define READ_STRING() AS_STRING(READ_CONSTANT())

#define BINARY_OP(valueType, op) \

It reads a one-byte operand from the bytecode chunk. It treats that as an index into the chunk’s constant table and returns the string at that index. It doesn’t check that the value is a string—it just indiscriminately casts it. That’s safe because the compiler never emits an instruction that refers to a non-string constant. 它从字节码块中读取一个1字节的操作数。它将其视为字节码块的常量表的索引,并返回该索引处的字符串。它不检查该值是否是字符串—它只是不加区分地进行类型转换。这是安全的,因为编译器永远不会发出引用非字符串常量的指令。

Because we care about lexical hygiene, we also undefine this macro at the end of the interpret function. 因为我们关心词法卫生,所以在解释器函数的末尾也取消了这个宏的定义。

#undef READ_CONSTANT

in run()

#undef READ_STRING

#undef BINARY_OP

I keep saying “the hash table”, but we don’t actually have one yet. We need a place to store these globals. Since we want them to persist as long as clox is running, we store them right in the VM. 我一直在说“哈希表”,但实际上我们还没有哈希表。我们需要一个地方来存储这些全局变量。因为我们希望它们在clox运行期间一直存在,所以我们将它们之间存储在虚拟机中。

Value* stackTop;

in struct VM

Table globals;

Table strings;

As we did with the string table, we need to initialize the hash table to a valid state when the VM boots up. 正如我们对字符串表所做的那样,我们需要在虚拟机启动时将哈希表初始化为有效状态。

vm.objects = NULL;

in initVM()

initTable(&vm.globals);

initTable(&vm.strings);

And we tear it down when we exit. 当我们退出时,就将其删掉。

void freeVM() {

in freeVM()

freeTable(&vm.globals);

freeTable(&vm.strings);

As usual, we want to be able to disassemble the new instruction too. 跟往常一样,我们也希望能够对新指令进行反汇编。

return simpleInstruction("OP_POP", offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL: return constantInstruction("OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL", chunk, offset);

case OP_EQUAL:

And with that, we can define global variables. Not that users can tell that they’ve done so, because they can’t actually use them. So let’s fix that next. 有了这个,我们就可以定义全局变量了。但用户并不能说他们可以定义全局变量,因为他们实际上还不能使用这些变量。所以,接下来我们解决这个问题。

21 . 3读取变量

As in every programming language ever, we access a variable’s value using its name. We hook up identifier tokens to the expression parser here: 像所有编程语言中一样,我们使用变量的名称来访问它的值。我们在这里将标识符和表达式解析器进行挂钩:

[TOKEN_LESS_EQUAL] = {NULL, binary, PREC_COMPARISON},

replace 1 line

[TOKEN_IDENTIFIER] = {variable, NULL, PREC_NONE},

[TOKEN_STRING] = {string, NULL, PREC_NONE},

That calls this new parser function: 这里调用了这个新解析器函数:

add after string()

static void variable() { namedVariable(parser.previous); }

Like with declarations, there are a couple of tiny helper functions that seem pointless now but will become more useful in later chapters. I promise. 和声明一样,这里有几个小的辅助函数,现在看起来毫无意义,但在后面的章节中会变得更加有用。我保证。

add after string()

static void namedVariable(Token name) { uint8_t arg = identifierConstant(&name); emitBytes(OP_GET_GLOBAL, arg); }

This calls the same identifierConstant() function from before to take the

given identifier token and add its lexeme to the chunk’s constant table as a

string. All that remains is to emit an instruction that loads the global

variable with that name. Here’s the instruction:

这里会调用与之前相同的identifierConstant()函数,以获取给定的标识符标识,并将其词素作为字符串添加到字节码块的常量表中。剩下的工作就是生成一条指令,加载具有该名称的全局变量。下面是这个指令:

OP_POP,

in enum OpCode

OP_GET_GLOBAL,

OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL,

Over in the interpreter, the implementation mirrors OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL.

在解释器中,它的实现是OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL的镜像操作。

case OP_POP: pop(); break;

in run()

case OP_GET_GLOBAL: { ObjString* name = READ_STRING(); Value value; if (!tableGet(&vm.globals, name, &value)) { runtimeError("Undefined variable '%s'.", name->chars); return INTERPRET_RUNTIME_ERROR; } push(value); break; }

case OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL: {

We pull the constant table index from the instruction’s operand and get the variable name. Then we use that as a key to look up the variable’s value in the globals hash table. 我们从指令操作数中提取常量表索引并获得变量名称。然后我们使用它作为键,在全局变量哈希表中查找变量的值。

If the key isn’t present in the hash table, it means that global variable has never been defined. That’s a runtime error in Lox, so we report it and exit the interpreter loop if that happens. Otherwise, we take the value and push it onto the stack. 如果该键不在哈希表中,就意味着这个全局变量从未被定义过。这在Lox中是运行时错误,所以如果发生这种情况,我们要报告错误并退出解释器循环。否则,我们获取该值并将其压入栈中。

return simpleInstruction("OP_POP", offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_GET_GLOBAL: return constantInstruction("OP_GET_GLOBAL", chunk, offset);

case OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL:

A little bit of disassembling, and we’re done. Our interpreter is now able to run code like this: 稍微反汇编一下,就完成了。我们的解释器现在可以运行这样的代码了:

var beverage = "cafe au lait"; var breakfast = "beignets with " + beverage; print breakfast;

There’s only one operation left. 只剩一个操作了。

21 . 4赋值

Throughout this book, I’ve tried to keep you on a fairly safe and easy path. I don’t avoid hard problems, but I try to not make the solutions more complex than they need to be. Alas, other design choices in our bytecode compiler make assignment annoying to implement. 在这本书中,我一直试图让你走在一条相对安全和简单的道路上。我并不回避困难的问题,但是我尽量不让解决方案过于复杂。可惜的是,我们的字节码编译器中的其它设计选择使得赋值的实现变得很麻烦。

Our bytecode VM uses a single-pass compiler. It parses and generates bytecode on the fly without any intermediate AST. As soon as it recognizes a piece of syntax, it emits code for it. Assignment doesn’t naturally fit that. Consider: 我们的字节码虚拟机使用的是单遍编译器。它在不需要任何中间AST的情况下,动态地解析并生成字节码。一旦它识别出某个语法,它就会生成对应的字节码。赋值操作天然不符合这一点。请考虑一下:

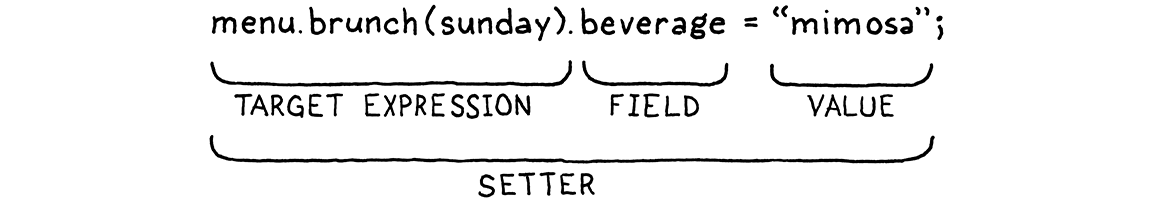

menu.brunch(sunday).beverage = "mimosa";

In this code, the parser doesn’t realize menu.brunch(sunday).beverage is the

target of an assignment and not a normal expression until it reaches =, many

tokens after the first menu. By then, the compiler has already emitted

bytecode for the whole thing.

在这段代码中,直到解析器遇见=(第一个menu之后很多个标识),它才能意识到menu.brunch(sunday).beverage是赋值操作的目标,而不是常规的表达式。到那时,编译器已经为整个代码生成字节码了。

The problem is not as dire as it might seem, though. Look at how the parser sees that example: 不过,这个问题并不像看上去那么可怕。看看解析器是如何处理这个例子的:

Even though the .beverage part must not be compiled as a get expression,

everything to the left of the . is an expression, with the normal expression

semantics. The menu.brunch(sunday) part can be compiled and executed as usual.

尽管.beverage部分无法被编译为一个get表达式,.左侧的其它部分是一个表达式,有着正常的表达式语义。menu.brunch(sunday)部分可以像往常一样编译和执行。

Fortunately for us, the only semantic differences on the left side of an

assignment appear at the very right-most end of the tokens, immediately

preceding the =. Even though the receiver of a setter may be an arbitrarily

long expression, the part whose behavior differs from a get expression is only

the trailing identifier, which is right before the =. We don’t need much

lookahead to realize beverage should be compiled as a set expression and not a

getter.

幸运的是,赋值语句左侧部分唯一的语义差异在于其最右侧的标识,紧挨着=之前。尽管setter的接收方可能是一个任意长的表达式,但与get表达式不同的部分在于尾部的标识符,它就在=之前。我们不需要太多的前瞻就可以意识到beverage应该被编译为set表达式而不是getter。

Variables are even easier since they are just a single bare identifier before an

=. The idea then is that right before compiling an expression that can also

be used as an assignment target, we look for a subsequent = token. If we see

one, we compile it as an assignment or setter instead of a variable access or

getter.

变量就更简单了,因为它们在=之前就是一个简单的标识符。那么我们的想法是,在编译一个也可以作为赋值目标的表达式之前,我们会寻找随后的=标识。如果我们看到了,那表明我们将其一个赋值表达式或setter来编译,而不是变量访问或getter。

We don’t have setters to worry about yet, so all we need to handle are variables. 我们还不需要考虑setter,所以我们需要处理的就是变量。

uint8_t arg = identifierConstant(&name);

in namedVariable()

replace 1 line

if (match(TOKEN_EQUAL)) { expression(); emitBytes(OP_SET_GLOBAL, arg); } else { emitBytes(OP_GET_GLOBAL, arg); }

}

In the parse function for identifier expressions, we look for an equals sign after the identifier. If we find one, instead of emitting code for a variable access, we compile the assigned value and then emit an assignment instruction. 在标识符表达式的解析函数中,我们会查找标识符后面的等号。如果找到了,我们就不会生成变量访问的代码,我们会编译所赋的值,然后生成一个赋值指令。

That’s the last instruction we need to add in this chapter. 这就是我们在本章中需要添加的最后一条指令。

OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL,

in enum OpCode

OP_SET_GLOBAL,

OP_EQUAL,

As you’d expect, its runtime behavior is similar to defining a new variable. 如你所想,它的运行时行为类似于定义一个新变量。

}

in run()

case OP_SET_GLOBAL: { ObjString* name = READ_STRING(); if (tableSet(&vm.globals, name, peek(0))) { tableDelete(&vm.globals, name); runtimeError("Undefined variable '%s'.", name->chars); return INTERPRET_RUNTIME_ERROR; } break; }

case OP_EQUAL: {

The main difference is what happens when the key doesn’t already exist in the globals hash table. If the variable hasn’t been defined yet, it’s a runtime error to try to assign to it. Lox doesn’t do implicit variable declaration. 主要的区别在于,当键在全局变量哈希表中不存在时会发生什么。如果这个变量还没有定义,对其进行赋值就是一个运行时错误。Lox不做隐式的变量声明。

The other difference is that setting a variable doesn’t pop the value off the stack. Remember, assignment is an expression, so it needs to leave that value there in case the assignment is nested inside some larger expression. 另一个区别是,设置变量并不会从栈中弹出值。记住,赋值是一个表达式,所以它需要把这个值保留在那里,以防赋值嵌套在某个更大的表达式中。

Add a dash of disassembly: 加一点反汇编代码:

return constantInstruction("OP_DEFINE_GLOBAL", chunk,

offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_SET_GLOBAL: return constantInstruction("OP_SET_GLOBAL", chunk, offset);

case OP_EQUAL:

So we’re done, right? Well . . . not quite. We’ve made a mistake! Take a gander at: 我们已经完成了,是吗?嗯……不完全是。我们犯了一个错误!看一下这个:

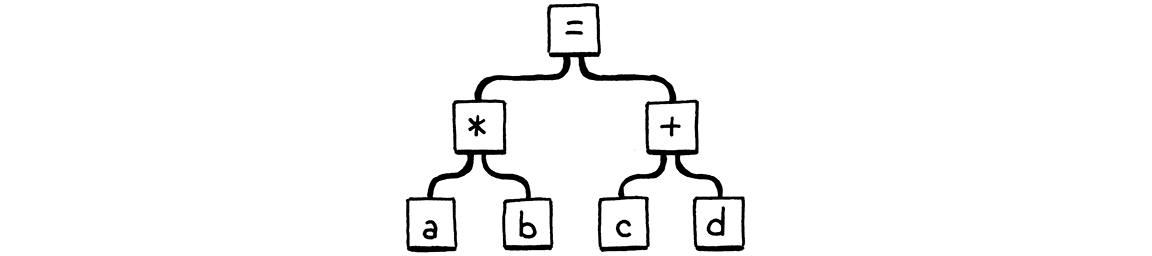

a * b = c + d;

According to Lox’s grammar, = has the lowest precedence, so this should be

parsed roughly like:

根据Lox语法,=的优先级最低,所以这大致应该解析为:

Obviously, a * b isn’t a valid assignment target, so

this should be a syntax error. But here’s what our parser does:

显然,a*b不是一个有效的赋值目标,所以这应该是一个语法错误。但我们的解析器是这样的:

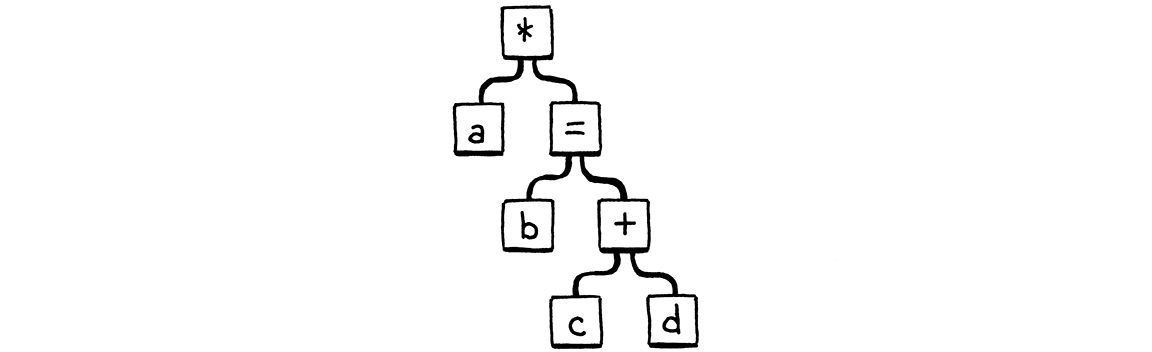

- First,

parsePrecedence()parsesausing thevariable()prefix parser. - After that, it enters the infix parsing loop.

- It reaches the

*and callsbinary(). - That recursively calls

parsePrecedence()to parse the right-hand operand. - That calls

variable()again for parsingb. - Inside that call to

variable(), it looks for a trailing=. It sees one and thus parses the rest of the line as an assignment.

- 首先,

parsePrecedence()使用variable()前缀解析器解析a。 - 之后,会进入中缀解析循环。

- 达到

*,并调用binary()。 - 递归地调用

parsePrecedence()解析右操作数。 - 再次调用

variable()解析b。 - 在对

variable()的调用中,会查找尾部的=。它看到了,因此会将本行的其余部分解析为一个赋值表达式。

In other words, the parser sees the above code like: 换句话说,解析器将上面的代码看作:

We’ve messed up the precedence handling because variable() doesn’t take into

account the precedence of the surrounding expression that contains the variable.

If the variable happens to be the right-hand side of an infix operator, or the

operand of a unary operator, then that containing expression is too high

precedence to permit the =.

我们搞砸了优先级处理,因为variable()没有考虑包含变量的外围表达式的优先级。如果变量恰好是中缀操作符的右操作数,或者是一元操作符的操作数,那么这个包含表达式的优先级太高,不允许使用=。

To fix this, variable() should look for and consume the = only if it’s in

the context of a low-precedence expression. The code that knows the current

precedence is, logically enough, parsePrecedence(). The variable() function

doesn’t need to know the actual level. It just cares that the precedence is low

enough to allow assignment, so we pass that fact in as a Boolean.

为了解决这个问题,variable()应该只在低优先级表达式的上下文中寻找并使用=。从逻辑上讲,知道当前优先级的代码是parsePrecedence()。variable()函数不需要知道实际的级别。它只关心优先级是否低到允许赋值表达式,所以我们把这个情况以布尔值传入。

error("Expect expression.");

return;

}

in parsePrecedence()

replace 1 line

bool canAssign = precedence <= PREC_ASSIGNMENT; prefixRule(canAssign);

while (precedence <= getRule(parser.current.type)->precedence) {

Since assignment is the lowest-precedence expression, the only time we allow an assignment is when parsing an assignment expression or top-level expression like in an expression statement. That flag makes its way to the parser function here: 因为赋值是最低优先级的表达式,只有在解析赋值表达式或如表达式语句等顶层表达式时,才允许出现赋值。这个标志会被传入这个解析器函数:

function variable()

replace 3 lines

static void variable(bool canAssign) { namedVariable(parser.previous, canAssign); }

Which passes it through a new parameter: 通过一个新参数透传该值:

function namedVariable()

replace 1 line

static void namedVariable(Token name, bool canAssign) {

uint8_t arg = identifierConstant(&name);

And then finally uses it here: 最后在这里使用它:

uint8_t arg = identifierConstant(&name);

in namedVariable()

replace 1 line

if (canAssign && match(TOKEN_EQUAL)) {

expression();

That’s a lot of plumbing to get literally one bit of data to the right place in

the compiler, but arrived it has. If the variable is nested inside some

expression with higher precedence, canAssign will be false and this will

ignore the = even if there is one there. Then namedVariable() returns, and

execution eventually makes its way back to parsePrecedence().

为了把字面上的1比特数据送到编译器的正确位置需要做很多工作,但它已经到达了。如果变量嵌套在某个优先级更高的表达式中,canAssign将为false,即使有=也会被忽略。然后namedVariable()返回,执行最终返回到了parsePrecedence()。

Then what? What does the compiler do with our broken example from before? Right

now, variable() won’t consume the =, so that will be the current token. The

compiler returns back to parsePrecedence() from the variable() prefix parser

and then tries to enter the infix parsing loop. There is no parsing function

associated with =, so it skips that loop.

然后呢?编译器会对我们前面的负面例子做什么?现在,variable()不会消耗=,所以它将是当前的标识。编译器从variable()前缀解析器返回到parsePrecedence(),然后尝试进入中缀解析循环。没有与=相关的解析函数,因此也会跳过这个循环。

Then parsePrecedence() silently returns back to the caller. That also isn’t

right. If the = doesn’t get consumed as part of the expression, nothing else

is going to consume it. It’s an error and we should report it.

然后parsePrecedence()默默地返回到调用方。这也是不对的。如果=没有作为表达式的一部分被消耗,那么其它任何东西都不会消耗它。这是一个错误,我们应该报告它。

infixRule(); }

in parsePrecedence()

if (canAssign && match(TOKEN_EQUAL)) { error("Invalid assignment target."); }

}

With that, the previous bad program correctly gets an error at compile time. OK, now are we done? Still not quite. See, we’re passing an argument to one of the parse functions. But those functions are stored in a table of function pointers, so all of the parse functions need to have the same type. Even though most parse functions don’t support being used as an assignment target—setters are the only other one—our friendly C compiler requires them all to accept the parameter. 这样,前面的错误程序在编译时就会正确地得到一个错误。好了,现在我们完成了吗?也不尽然。看,我们正向一个解析函数传递参数。但是这些函数是存储在一个函数指令表格中的,所以所有的解析函数需要具有相同的类型。尽管大多数解析函数都不支持被用作赋值目标—setter是唯一的一个—但我们这个友好的C编译器要求它们都接受相同的参数。

So we’re going to finish off this chapter with some grunt work. First, let’s go ahead and pass the flag to the infix parse functions. 所以我们要做一些苦差事来结束这一章。首先,让我们继续前进,将标志传给中缀解析函数。

ParseFn infixRule = getRule(parser.previous.type)->infix;

in parsePrecedence()

replace 1 line

infixRule(canAssign);

}

We’ll need that for setters eventually. Then we’ll fix the typedef for the function type. 我们最终会在setter中需要它。然后,我们要修复函数类型的类型定义。

} Precedence;

add after enum Precedence

replace 1 line

typedef void (*ParseFn)(bool canAssign);

typedef struct {

And some completely tedious code to accept this parameter in all of our existing parse functions. Here: 还有一些非常乏味的代码,为了在所有的现有解析函数中接受这个参数。这里:

function binary()

replace 1 line

static void binary(bool canAssign) {

TokenType operatorType = parser.previous.type;

And here: 这里:

function literal()

replace 1 line

static void literal(bool canAssign) {

switch (parser.previous.type) {

And here: 这里:

function grouping()

replace 1 line

static void grouping(bool canAssign) {

expression();

And here: 这里:

function number()

replace 1 line

static void number(bool canAssign) {

double value = strtod(parser.previous.start, NULL);

And here too: 还有这里:

function string()

replace 1 line

static void string(bool canAssign) {

emitConstant(OBJ_VAL(copyString(parser.previous.start + 1,

And, finally: 最后:

function unary()

replace 1 line

static void unary(bool canAssign) {

TokenType operatorType = parser.previous.type;

Phew! We’re back to a C program we can compile. Fire it up and now you can run this: 吁!我们又回到了可以编译的C程序。启动它,新增你可以运行这个:

var breakfast = "beignets"; var beverage = "cafe au lait"; breakfast = "beignets with " + beverage; print breakfast;

It’s starting to look like real code for an actual language! 它开始看起来像是实际语言的真正代码了!

Challenges

-

The compiler adds a global variable’s name to the constant table as a string every time an identifier is encountered. It creates a new constant each time, even if that variable name is already in a previous slot in the constant table. That’s wasteful in cases where the same variable is referenced multiple times by the same function. That, in turn, increases the odds of filling up the constant table and running out of slots since we allow only 256 constants in a single chunk. 每次遇到标识符时,编译器都会将全局变量的名称作为字符串添加到常量表中。它每次都会创建一个新的常量,即使这个变量的名字已经在常量表中的前一个槽中存在。在同一个函数多次引用同一个变量的情况下,这是一种浪费。这反过来又增加了填满常量表的可能性,因为我们在一个字节码块中只允许有256个常量。

Optimize this. How does your optimization affect the performance of the compiler compared to the runtime? Is this the right trade-off? 对此进行优化。与运行时相比,你的优化对编译器的性能有何影响?这是正确的取舍吗?

-

Looking up a global variable by name in a hash table each time it is used is pretty slow, even with a good hash table. Can you come up with a more efficient way to store and access global variables without changing the semantics? 每次使用全局变量时,根据名称在哈希表中查找变量是很慢的,即使有一个很好的哈希表。你能否想出一种更有效的方法来存储和访问全局变量而不改变语义?

-

When running in the REPL, a user might write a function that references an unknown global variable. Then, in the next line, they declare the variable. Lox should handle this gracefully by not reporting an “unknown variable” compile error when the function is first defined. 当在REPL中运行时,用户可能会编写一个引用未知全局变量的函数。然后,在下一行中,他们声明了这个变量。Lox应该优雅地处理这个问题,在第一次定义函数时不报告“未知变量”的编译错误。

But when a user runs a Lox script, the compiler has access to the full text of the entire program before any code is run. Consider this program: 但是,当用户运行Lox脚本时,编译器可以在任何代码运行之前访问整个程序的全部文本。考虑一下这个程序:

fun useVar() { print oops; } var ooops = "too many o's!";

Here, we can tell statically that

oopswill not be defined because there is no declaration of that global anywhere in the program. Note thatuseVar()is never called either, so even though the variable isn’t defined, no runtime error will occur because it’s never used either. 这里,我们可以静态地告知用户oops不会被定义,因为在程序中 没有 任何地方对该全局变量进行了声明。请注意,useVar()也从未被调用,所以即使变量没有被定义,也不会发生运行时错误,因为它从未被使用。We could report mistakes like this as compile errors, at least when running from a script. Do you think we should? Justify your answer. What do other scripting languages you know do? 我们可以将这样的错误报告为编译错误,至少在运行脚本时是这样。你认为我们应该这样做吗?请说明你的答案。你知道其它脚本语言是怎么做的吗?